Review: The Sky Aboveby Jeff Foust Review: The Sky Aboveby Jeff FoustMonday, May 2, 2022 The Sky Above: An Astronaut’s Memoir of Adventure, Persistence, and Faith by John Casper Purdue University Press, 2022 hardcover, 306 pp., illus. ISBN 978-1-61249-716-7 US$27.99In retrospect, the 1990s were something of a golden age for the shuttle program. At the beginning of the decade, the shuttle was getting back up to speed after recovering from the Challenger accident. By the end of the decade, it was flying regularly, having demonstrated the key capabilities needed for assembling the International Space Station, along the way doing research missions while also deploying and servicing the Hubble Space Telescope. But, perhaps, that era was also laying the groundwork for the Columbia accident that would follow in 2003.That steady flow of shuttle missions created a lot of flight opportunities for astronauts, many of whom flew with little public attention. Among them is John Casper, who flew on four shuttle missions, commanding three of them, in the early to mid-1990s. In his memoir The Sky Above, he describes the path that led to him becoming an astronaut and his experience at NASA both during and after those shuttle missions.Casper recalls he was interested in becoming an astronaut since he was 10 years old, before anyone had even gone into space. That interest guided his plans for decades, which led him to the Air Force Academy, training as a fighter pilot, a tour of service in Vietnam and, later, test pilot school, a path that many others followed to become astronauts. But, when he applied in 1977, he was told he was medically disqualified because of borderline hypertension. He decided, though, to take one more shot about five years later, when he was in a staff job at the Pentagon. “Otherwise, you’ll always wonder if you could have made it if you tried one more time,” a colleague advised him. He did, and after working with NASA to address the hypertension issue, was selected.“Otherwise, you’ll always wonder if you could have made it if you tried one more time,” a colleague advised Casper when he considered applying again to be a NASA astronaut.He was able, once at NASA, to fly frequently thanks to the relative high rate of missions (at least compared to today, not to the far more optimistic projections of the early shuttle program) of the era: his first flight, as pilot of a DOD mission, launched in February 1990, and his fourth and final mission in May 1996. None of the missions stood out—no Hubble repair or Shuttle-Mir dockings, for example—but illustrated the other range of missions, like microgravity research and technology demonstration, that the shuttle performed in that era.After his final shuttle flight, Casper remained at the agency as a safety director at the Johnson Space Center, dealing with issues involving the shuttle and station programs. While the shuttle program “was just hitting its stride” in the late 1990s, he recalled, budget cuts were causing a loss of personnel and growing concerns about safety. (Casper blames the cuts on the Clinton Administration, but those cuts were also included in spending bills passed by Congresses with Republican majorities.) After the incidents on the STS-93 launch in 1999, which included a short circuit caused a wire defect, he recalled pushing for inspections of the wiring on other orbits, only to face opposition from others on the shuttle program control board who worried about launch delays. Only after more flaws were found in “quick-look” inspections was the wiring in all four orbiters thoroughly checked.NASA would run out of luck with Columbia a few years later, although foam shedding had been a problem for years (Casper said he found out only after the accident that form had come off the same location on the external tank on one of his launches, fortunately not hitting the orbiter.) He supported the investigation and then held managerial positions through the end of the shuttle program and then Orion before retiring shortly after the EFT-1 mission in late 2014.Casper tells a thorough, and interesting, story of his life in The Sky Above, including the setbacks he encountered along the way and, as the subtitle suggests, how his religious faith offered guidance through difficult times. It illustrates, among other things, how active the shuttle program was in the era when he was an astronaut, but how that activity could mask, or even lead to, deeper problems down the road.Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone. |

Month: May 2022

Lessons From A New Era Of Destinations!

A Crww Dragon spacecraft splashes down off the Florida coast April 25 to end the Ax-1 private astronaut mission to the ISS. (credit: SpaceX) A Crww Dragon spacecraft splashes down off the Florida coast April 25 to end the Ax-1 private astronaut mission to the ISS. (credit: SpaceX) |

Lessons from a new era of destinations

by Jeff Foust

Monday, May 2, 2022

A delayed flight home is usually a bad thing—unless, perhaps, you’re in space.

| “Here we are at the conclusion of an incredible mission, and I must say the teams exceeded every expectation,” Axiom’s Blachman said. |

The four private astronauts on Axiom Space’s Ax-1 mission arrived at the International Space Station April 9 on a Crew Dragon spacecraft for what was supposed to be an eight-day stay. Instead, the four remained on the station for more than 15 days before departing late April 24, safely splashing down the next day off the coast from Jacksonville, Florida.

The Ax-1 crew got effectively a free extra week on the ISS because of poor weather at splashdown locations in both the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. “We had a pattern of high winds that affected all of our various potential landing sites,” said Benji Reed, senior director of human spaceflight programs at SpaceX, in a call with reporters after splashdown.

Despite the delay, Axiom called the mission, the first private astronaut mission to the ISS by a US spacecraft, a success. “Here we are at the conclusion of an incredible mission, and I must say the teams exceeded every expectation,” Amir Blachman, chief business officer of Axiom Space, said after splashdown. “We could not be more proud of what has just been accomplished.”

The mission was the latest step in a long-term plan by NASA and industry to transition from the ISS to commercial stations by the end of the decade. Those private astronaut missions to the ISS are intended to prime the pump for more ambitious commercial activities on a commercial module Axiom plans to add to the ISS in the middle of the decade and, later, commercial space stations being developed by Axiom and others.

It also illustrated some the challenges of that mission. For example, did the extended stay of Ax-1 at the ISS mean NASA would charge Axiom more money for life support and other services? Would that charge then be passed on to the three customers, who each paid a rumored $55 million for the flight?

Axiom said that the company’s agreement with NASA included provisions for an extended stay, but declined to go into specifics. (The company has been reticent to discuss financial aspects of the mission, including whether the Ax-1 mission itself will make a profit.) NASA said that the agreement included “equitable balance” to cover delays like what Ax-1 experienced. “NASA negotiated the contract with a strategy that does not require reimbursement for additional undock delays,” agency spokesperson Stephanie Schierholz said.

The delayed return of Ax-1 also affected NASA’s Crew-4 mission, another Crew Dragon flight carrying NASA and ESA astronauts to the station for a long-duration stay. Crew-4 could not launch until after Ax-1 returned home, although NASA and SpaceX managed to successfully launch Crew-4 less than 39 hours after Ax-1 splashed down.

| “Our joint team had to make sure we weren’t going to screw anything up. We had to do it one step at a time, not in a hurry, making sure that we got it done,” Lueders said. |

“We started with a little more spacing than what you’re seeing here between the Axiom and the Crew-4 missions, and that’s always our goal, to space these things out, give you some time to work any issues you have,” said Joel Montalbano, NASA ISS program manager, last week. “One of the lessons learned out of this is to see if we can define a better spacing between the missions.”

He noted the program had to deal with not just the Ax-1 and Crew-4 missions, but working launches around the delayed SLS wet dress rehearsal, Russian spacewalks, and launches in May and June of a Boeing CST-100 Starliner on an uncrewed test flight and a SpaceX cargo Dragon mission. “Spaceflight tends to be a magnet of dynamic activities,” he said. “They all tend to draw together.”

“We learned a lot conducting that mission. We learned a lot about cadence,” Kathy Lueders, NASA associate administrator for space operations, said of Ax-1 in a talk Thursday at the AIAA ASCENDx Texas conference in Houston. “Our joint team had to make sure we weren’t going to screw anything up. We had to do it one step at a time, not in a hurry, making sure that we got it done.”

Those lessons from Ax-1 are valuable, both NASA and industry said, as they move into a future with more commercial activity on ISS and, eventually, commercial space stations. “We’ve had some early validation of the crewed market with the successful Ax-1 mission,” said Michael Baine, chief engineer and chief designer of Axiom Space, during a panel of commercial space station developers Wednesday at the AIAA conference. The company is looking ahead to its next crewed ISS mission, Ax-2, scheduled for early spring of 2023.

“I think that market is going to take off as we expect it to,” he said, adding the company was seeing “some early signs of life” from media and entertainment markets for its future commercial ISS modules and standalone space station.

One issue that he and others raised is the transition of research being done on the ISS to commercial platforms. “Every one of our business cases has assumptions in it about the fraction of the NASA market that we’re going to capture,” said Brent Sherwood, senior vice president of advanced development programs at Blue Origin. “I guarantee you that, if you add up all those fractions across this stage, it exceeds unity.”

He suggested NASA could help companies by providing more quantitative data about how it would divide up research currently being done on the ISS among two or more stations. “Having that quantified would help all of us.”

Jeffrey Manber, president of international and space stations at Voyager Space, said he’s still waiting to see more research emerge from customers other than NASA and other government agencies. “We don’t have that magical mix yet of industrial players,” he said. “We have to have that mix between the NASA-inspired research, US government research, and also, we’ve got to figure out the ways that get the overall industry involved.”

But the near-term success and the long-term optimism face a medium-term challenge: whether the ISS will last long enough to enable that transition to commercial space stations by the end of the decade. The Biden Administration formally endorsed at the end of last year an extension of the ISS through 2030, a move that Canada, Europe and Japan have also backed.

However, even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February severed most cooperation between the West and Russia in space outside of the ISS, Roscosmos had expressed skepticism about extending the ISS beyond 2024, citing what it thought was a growing cost to maintain the aging station.

Russia has not provided any clarity about its plans since then beyond occasional Russian media reports, such as one over the weekend where Dmitry Rogozin, head of Roscosmos, claimed that Russia had decided when to leave the ISS but “we’re not obliged to talk about it publicly” beyond it would not be before 2024. He added that, if and when Russia decided to exit the ISS partnership, he would give the other partners one year’s notice.

| “Ending that partnership is going to be a challenging thing,” Kelly said. “It would be hard for either country to operate the ISS without the other country.” |

NASA administrator Bill Nelson, speaking at a briefing before the Crew-4 launch last week, said he remained optimistic that Russia would remain part of the ISS partnership for the long term. He cited the “professional relationship” that continues between NASA and Roscosmos on day-to-day ISS operations.

“Despite the horrors that we are seeing with our eyes daily on television of what’s happening in Ukraine as the result of political decisions that are being made by the president of Russia,” Nelson said, “I see that professional relationship with astronauts and cosmonauts and the ground teams in the two respective mission controls continuing.”

At the McCain Institute’s Sedona Forum on Saturday, Sen. Mark Kelly (D-AZ), a former astronaut, said he talks regularly with Nelson and with NASA’s deputy administrator, Pam Melroy, on how the Ukraine crisis affects NASA and, specifically, the ISS. While NASA has not talked about contingency plans should Russia exit the ISS partnership in 2024, or any time before the retirement of the station, he suggested that NASA could turn to commercial cargo vehicles to provide the reboost of the station’s orbit that the station’s Russia segment currently handles.

“Ending that partnership is going to be a challenging thing,” he said. “It would be hard for either country to operate the ISS without the other country.”

He suggested there could be pressure from the US side to reexamine its partnership with Russia on the ISS as the West ratchets up sanctions on Russia. “Eventually we will have done everything and there will be one thing left, and that’s this partnership in space on ISS with them,” he said.

Those working on commercial space stations are focused on the long-term prospects, and that fact that such stations look more feasible now than ever. “We’re here talking about four private space stations. I’ve waited a long time for this,” Manber said on a panel that included Axiom, Blue Origin and Northrop Grumman. “This is a new era of destinations.”

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

The Future Of Human Space Exploration In Japan

A Japanese HTV cargo spacecraft departing the International Space Station, an example of the capabilities Japan has developed that could support future human exploration programs. (credit: NASA) A Japanese HTV cargo spacecraft departing the International Space Station, an example of the capabilities Japan has developed that could support future human exploration programs. (credit: NASA) |

Raising the flag on the Moon and Mars: future human space exploration in Japan (part 1)

by Makusu Tsuizaki

Monday, May 2, 2022

Japan has progressed in the development and utilization of space over the past 50 years. During this time, space activity has grown from academic research and technology interests to civil and industrial interests. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has been the single national organization for aerospace and space research, technology development, and performing launch of satellites, resulting from the 2003 merger of three previously independent organizations. In addition, the structure of government work for space policy has been changed and the Space Basic Plan was built as a “whole of government” approach. The Cabinet Office (CAO), created in 2012, has functioned to coordinate organizations across the relevant ministries and agencies related to space activities and manage some special committees composed of experts in space as a secretariat office. Through discussions in these committees, finally, the cabinet, consisting of all ministers with relevant roles, decides space policy.

| There is little clear policy and strategy inclusive in human exploration as a whole-of-government matter. |

The Space Basic Plan (main text and implementation plan), a comprehensive governmental space policy and strategy, has been revised periodically since the passage of the Space Basic Law in 2008, and the implementation plan has been revised almost every year recently. Current Prime Minister Kishida stated, “Space is a frontier that gives people dreams and hopes, and is also an important foundation that supports the economy and society from the perspective of economic security.” The latest revised Space Basic Plan makes several substantial points with respect to constellations of small satellites, research and development of optical satellite communications, promotion of the Artemis program, further development of space solar power generation, and international cooperation with the United States, Australia, and India (CAO, 2021).

Human space exploration in Japan began with the commitment to construction of the International Space Station (ISS) and operation (ISS IGA and ISS MOU, 1988) and has been a continuous part of international cooperation since then. In 2020, Japan signed the Artemis Accords with other cooperative countries and is collaborating with the Artemis program led by the United States, targeting the Moon, Mars, and other celestial bodies (The Artemis Accords, 2020). Japan just has started the selection for new astronauts for the ISS and next lunar exploration activities based on participation in the Artemis program.

Although the latest revised Space Basic Plan and some documents written by the Cabinet, the CAO, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) showed the strategic directions for the ISS, Moon, and Mars exploration in each standpoint, there is little clear policy and strategy inclusive in human exploration as a whole-of-government matter.

In an independent study, the author examined the motives and advantages of human space exploration in Japan and suggested an approach for future policy decision-making. Current Japanese policy is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: The directions of the ISS, Moon, and Mars exploration in recent policy documents in Japan

| ISS (and LEO) | *ISS would be a testbed of technological development for outer space exploration and should be shifted to industrial utilization and management. *Government should indicate the vision for the ISS and LEO related to international space exploration and induce “seamless” transition for commercial utilization. (MEXT, 2021) *Government should continuously discuss actions in the ISS and LEO after year 2025 with the understanding commercial participation capability and utilization of the ISS. (Space Basic Plan, implementation plan, 2021) |

| Moon | *Government should commit to the Artemis program based on the agreement with the United States, progress the Gateway program, and crewed pressurized rover or basic technologies cooperated with industry for continuous lunar activities. *Japan should aim for the first Japanese landing on the Moon in the latter half of 202’s. (Space Basic Plan, implementation plan, 2021) |

| Mars | With a perspective for future exploration of Mars, which is a goal of the Artemis program, government should progress exploration plans for the main planet of Mars, which will be tackled through international cooperation based on its importance in space science. (Space Basic Plan, implementation plan, 2021) |

| Astronauts | New crews are applied and selected for lunar exploration activities based on participation to the Artemis program. (Space Basic Plan, implementation plan, 2021) |

The advantages of progressing human space exploration in Japan

Japan has committed to international cooperation by sharing the common system operation costs and operating their original experimental module Kibo on the ISS and deciding to participate in the Artemis program. In the case of the ISS, the duration and order of astronaut crews are decided based on the contributions of each participant. Thanks to previous contributions by Japanese astronauts, forthcoming Japanese astronauts continuously play a pivotal role in ISS development and utilization and Japan has a major presence in international exploration projects. Therefore, the most visible benefit of human spaceflight should be that Japanese astronauts continue to be active in outer space, on the Moon, and Mars in the future.

In past activities, Japan has coordinated and encouraged cooperation with the United States, Canada, Russia, Europe, and other Asian countries. In addition to the ISS IGA, Japan has supported developing countries through a trial of new satellite experiments in the ISS, such as the “Kibo-Cube” program. These ongoing collaborations with many countries in the ISS will lead to future space exploration activities with international cooperation and keep a stable relationship between cooperative countries.

From some public viewpoints, the government should advance new technology and industrial development through space exploration. Japan has strengthened its technology base through participation in the ISS and original national projects (Table 2). Cutting-edge basic technologies for future space exploration, such as in-situ resource utilization or data sharing, have been developed in numerous countries and private companies all over the world. International cooperation and sharing of information takes advantage of each country’s strengths while working toward a common goal. As a result, it is possible to gain new knowledge and demonstrate technologies for future human space exploration between cooperating countries. In addition, scientific planetary research has sought to find knowledge of the nature of life. Since robotic exploration technologies for science missions, such as sample return or data collection from other planets, are closely related to future human missions, they will help promote human space exploration.

| How should Japan’s space policy balance international cooperation and the creation of autonomous national capabilities? |

These potential benefits would, in common, encourage stakeholders in space and increase national interest in Japan as well as international awareness. At the same time, these benefits will not be achieved without international cooperation because Japan does not have at least one of the essential technologies for human spaceflight: human-rated space launch vehicles. Such lack of independence in human space exploration comes with various risks, limitations on exploration activities with international commitments or legally binding agreements, and unstable economic or political situations in cooperating countries.

According to recent government policy documents, Japan has promoted human space exploration in international cooperation as much as possible from the viewpoint of cost-effectiveness. These documents also said that it is necessary to continue to acquire, accumulate, and prepare human space technologies centering on key technologies. Doing so will enable Japan to proceed with meaningful efforts in international cooperation that are self-sustaining and cost-effective for future crewed activities (MEXT, 2020).

How should Japan’s space policy balance international cooperation and the creation of autonomous national capabilities?

Table 2: Strong elements and key technologies regarding space exploration in Japan

| Strong elements | National projects (operation period) | Related key technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Human settlement | *ISS (1988-) *Gateway in the Artemis program (2019-) | *robotics *new material usage (space suits, batteries, etc.) *food supply*optical communication |

| Material supply to basecamp | *HTV (1997-2021) *HTV-X (2022-) | *cargo transportation *docking equipment and system |

| Landing on Moon | *SLIM (2022) | *small and light machinery *scanning technology in high resolution |

| Mobility on Moon | *LUPEX (2023) *pressurized rover development (2018- in progress) | *battery *automatic operation *navigation and communication system |

| Sample return from outer planet | *Hayabusa and Hayabusa 2 (2003-) *MMX (2024) *I-MIM (2026) | unique satellite bus and sensor |

Notes: Each project or program regarding space exploration was categorized in line with “Strong elements” shown in the government documents in this table. “Related key technologies” was shown based on each project or program outline referred in public. Note that there are also small-scale R&D that is not project-based (not shown in this table). These technological priorities were shown in a recent government document from the CAO: Deep space supply (rendezvous docking), manned space settlement (environment control), take-off and landing on gravity celestial body (high-precision navigation), surface exploration (surface movement, drilling, water, and ice analysis) (CAO, 2019)

Abbreviations: HTV (H-II Transfer Vehicle), SLIM (Smart Lander for Investigating Moon), LUPEX (Lunar Polar Exploration Mission), MMX (Martian Moons eXploration), I-MIM (International Mars Ice Mapper).

The best balance between international cooperation and independent implementation for Japan

As in the US-led Artemis program, it is necessary for the achievement of human Moon and Mars exploration to develop key technologies and build some advanced and essential facilities for launch, transportation, landing, mobility, and habitat systems in outer space (NASA, 2020).

Japan has been contributing to the ISS for more than 30 years and developing some key technologies and knowledge essential to human settlement. In addition, Japan has also decided to commit to the Joint Exploration Declaration of Intent for Lunar Cooperation (JEDI), Artemis Accords and Gateway MOU between the United States, and progressing on some programs with international collaboration (Table 2).

In terms of policymaking in Japan, the author would argue that government budgets and international cooperation are the most significant considerations.

Government budgets

To manage human space exploration, there are at least four conditions to consider given the current situation in Japan: 1) the budget allocation balance between ISS, Moon, and Mars projects, 2) the balance between human spaceflight and robotic space planetary science in JAXA, 3) MEXT/JAXA budget and other ministries’ and agencies’ budgets, 4) the priority between international cooperation and national security.

1) The budget allocation balance between ISS, Moon, and Mars projects

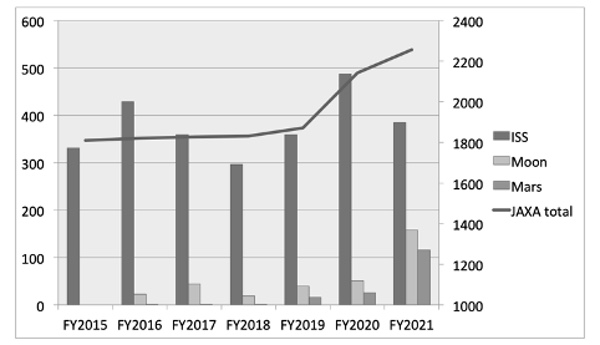

The profile of the recent seven years (FY2015–2021) budget of the ISS, Moon, and Mars projects is shown in Fig. 1. Reflecting on the declaration for participation in the Artemis program in 2019 and the assignment of the Artemis Accords in 2020, all human exploration-related budgets and the JAXA total budget were larger in FY2020 and FY2021 than the former years. The ratio of the former years’ budget was 114% and 105% (JAXA total budget), and 136% and 117% (human exploration budget), in FY2020 and FY2021, respectively. One thing worth mentioning is that the ISS budget has included HTV or HTV-X, a unique material supply vehicle for the ISS, which also will be used for supply for the Gateway construction and operation is strongly linked to the Moon budget.

Figure 1 Human space exploration budget as of FY2021 in Japan. The budget amount for each year was the sum of the original budget and the previous year’s supplementary budget. The right side scale was for JAXA total budget (unit: 100 million Yen), and the left side scale was for ISS, Moon, and Mars projects or programs (unit: 100 million Yen). Each category included the following budget of projects or programs; JEM (Japanese Experiment Module) operation spending (FY2015-FY2021), HTV (FY2015-FY2020), and HTV-X (FY2016-FY2021) in “ISS”; SLIM (FY2016-FY2021), pressure rover development (FY2018-FY2021), contribution to the Gateway (FY2019-FY2021), and LUPEX (FY2020-FY2021) in “Moon”; MMX (FY2016-FY2021) in “Mars” Figure 1 Human space exploration budget as of FY2021 in Japan. The budget amount for each year was the sum of the original budget and the previous year’s supplementary budget. The right side scale was for JAXA total budget (unit: 100 million Yen), and the left side scale was for ISS, Moon, and Mars projects or programs (unit: 100 million Yen). Each category included the following budget of projects or programs; JEM (Japanese Experiment Module) operation spending (FY2015-FY2021), HTV (FY2015-FY2020), and HTV-X (FY2016-FY2021) in “ISS”; SLIM (FY2016-FY2021), pressure rover development (FY2018-FY2021), contribution to the Gateway (FY2019-FY2021), and LUPEX (FY2020-FY2021) in “Moon”; MMX (FY2016-FY2021) in “Mars” |

As of now, almost all spending on projects for the ISS, Moon, and Mars have been provided to JAXA through MEXT. The ISS is scheduled to be sustained through 2024 and could be extended to 2030. It has been mentioned that NASA would allow one or more commercial firms to own its share of the ISS or a LEO station in the future, at least from 2028. The ISS operation in the future is pending, however, it would be unrealistic for Japan to proceed with Moon and Mars exploration while operating the ISS at current costs. Under the international agreement, Japan might keep governmental responsibility for only critical contributions for sustaining the ISS.

| There is not enough funding for future long-term human space exploration with only the current MEXT/JAXA budget. |

With regards to the balance of JAXA’s budget, it could be affordable to focus on development and utilization of the Gateway or basic leading technologies for future human space exploration, and then a financial shift to Moon and Mars exploration. In recent years, JAXA has developed more potential research projects such as basic space exploration technology in a wide range of unexplored areas such as automatic and autonomous technology, and also named a “innovation hub for space exploration” program. It is effective to develop unique technologies from these programs into larger future projects.

2) The balance between human spaceflight and robotic space planetary science

How to keep the balance between human spaceflight and space science has been discussed earlier (Takashi Uchino, 2019) and some programs for international collaboration are intended to include both civil and scientific perspectives. Generally speaking, space science missions are often small-scale at first and require longer-term research. For this reason, a certain amount of budget has been set aside in the JAXA budget for space planetary science. While lunar exploration is focused on human activities, Mars exploration currently emphasizes robotic scientific activities. Basic scientific research findings and development will promote technological progress for another space program in many cases. For example, the Japanese-leading international Mars exploration project, MMX (Martian Moons eXploration), targets not only the exploration of the satellites of Mars but also the measurement of environmental radiation in the outer planets, which contributes to human settlement technology. To establish the goal of Mars human exploration, it is suggested to keep a continuous discussion with the science community and build advanced programs in the future.

3) MEXT/JAXA budget and other ministries’ and agencies’ budgets

There is not enough funding for future long-term human space exploration with only the current MEXT/JAXA budget, according to the author’s understanding from MEXT and JAXA. In Japan, the CAO was built in 2012 as the new organizational structure to be in charge of space policy. At present, in addition to the MEXT, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) can also support JAXA, and all ministers could commit to decisions of national space policy. As a result of the implementation of a comprehensive national space policy, more Ministries and Agencies have committed to support the Japanese space program. In recent years, for example, the MIC has committed to the development of positioning and communication technology for lunar activities, and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) has started the development of an advanced resource-circulating food supply system to support long-term stays on the Moon. Given the need for more ministries and agencies to be involved in space exploration, it is expected the CAO lead a stronger initiative for overall progress in this field. This will be discussed in part two.

4) The priority between international cooperation and national security

National security is one of the most important areas of space policy in Japan today, including the construction of satellite constellations and space situational awareness (SSA) through international cooperation as in other countries. Many countries have been expanding their activities in outer space and it is necessary to consider space exploration efforts that are not necessarily directly related to their national security but are nonetheless tied together.

For example, sharing information with other countries about planetary exploration will lead to safer activities for astronauts on those planets. Also, cases such as lunar resource utilization or operations by astronauts’ activity on the Moon remind us to consider who has the rights to use resources in outer space or who should exercise jurisdiction over astronauts. Although it is legally required in the Outer Space Treaty and the Artemis Accords that space exploration be only for peaceful purposes, some states might insist on their right to utilize and dominate outer space in the future. This topic has been part of various arguments for outer space regulation in bilateral and multilateral forums.

In addition, in Japan, the new minister in charge of economic security (including national security perspectives) has been named in 2021 for the first time, Takayuki Kobayashi, and he is also engaged in science and technology policy inclusive of space policy. This political situation suggests a deeper connection between national security and science and technology policy in Japan. Under these circumstances, it is important to consider how human space exploration contributes and affects to enhance national security. These perspectives should not be thought of as trade-offs but as correlations for mutual understanding, as will be discussed later.

References

The CAO, Space Basic Plan, summary of revision and revised implementation plan (2021), (in Japanese)

ISS IGA (1988): Agreement Among The Government Of Canada, Governments Of Member States Of The European Space Agency, The Government Of Japan The Government Of The Russian Federation, And The Government Of The United States Of America

ISS MOU (1988): Memorandum Of Understanding Between The National Aeronautics And Space Administration Of The United States Of America And The Government Of Japan Concerning Cooperation On The Civil International Space Station

The Artemis Accords (2020)

The MEXT, What the ISS or LEO should be? (Interim report)(2021), (in Japanese)

The MEXT, Human space exploration in Japan (2020), (in Japanese)

The CAO, Japan’s Participation Policy in International Space Exploration Proposed by the United States (2019), (in Japanese)

NASA, Artemis Plan, NASA’s Lunar Exploration Program Overview (2020)

Takashi Uchino, “What should be Japan’s strategy for human space exploration?”, The Space Review (2019)

International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) Agreement (2007)

Masaki Takata and Wataru Utsumi, The Next Generation 3GeV Synchrotron Radiation Facility Project in Japan, Facts and info from the European Physical Society (2019)

ESA, Terrae Novae 2030+ Strategy Roadmap (2021)

Takuya Wakimoto, A Guide to Japan’s Space Policy Formulation: Structures, Roles and Strategies of Ministries and Agencies for Space, Pacific Forum Working Paper (2019)

National Space Council, A New Era for Deep Space Exploration and Development (2020)

Takashi Uchino, A comparison of American and Japanese space policy structures, The Space Review (2018)

STIG (Science, Technology, and Innovation Governance) Education and Research Program, The University of Tokyo, The Future of Lunar and Cislunar Activities: Commercial, Governance & Security Challenges (2022)

European Space Policy Institute (ESPI), New Space in Asia (2021)

CNSP, Space Industry Vision for 2030 (2017), (in Japanese)

Walter Peeters, Evolution of the Space Economy: Government Space to Commercial Space and New Space, Astropolitics (2022)

Jeff Foust, “Japan passes space resources law,” Space News (2021)

Makusu Tsuizaki is a Visiting Scholar at George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

We Need A Solid Contingency Plan For Russia Non-Partiocipation In The ISS!!

Act now on contingencies for Russian non-participation in ISS

by Srikanth Raviprasad and Steve Hoeser

Monday, May 2, 2022

The International Space Station (ISS) has for decades been a pinnacle of human scientific, technological and political achievement. It remains the sole example of how an international team can productively and successfully cooperate over the course of decades in space.[1] Yet recent demands from Russia threaten the safety of ISS, people on Earth, and the cooperative mission objectives, including the transition to commercial space facility operations. This essay explores the importance of promptly responding to this concern and how NASA and other US agencies could mitigate risks. The two actions proposed here, which are not mutually exclusive, are:

- NASA creates a detailed plan describing the options to ensure survival of the ISS in the short term and cover all contingencies therein.

- NASA enhances progress toward replacing the ISS by providing non-monetary technical and NASA facility assistance to all US commercial space station providers while working with other government stakeholders to remove bureaucratic and regulatory encumbrances that could hamper the establishment of US commercial space habitat industry.

Importance of the ISS

The ISS has served as a partnership of nations performing research since 1998. It has elevated humanity’s sphere of influence into a new frontier and redefined what it means to be human. It has given us a foothold in space to begin expanding our commerce, culture, and civilization beyond the confines of Earth.

ISS research has provided invaluable insights on many critical human and technological domains. Just a few include fundamental disease research, advanced water purification systems, and the existence of commercial space markets. Furthermore, ISS successes have bolstered participating nations’ credibility, influence, and leadership in the peaceful use of space worldwide.[2]

| Any space station gap could jeopardize the strong network of international partnerships and enterprises that have been in place over the last two decades and could halt their continuing maturation. |

After more than two decades of fundamental research and technology development there, the ISS has entered an evolved phase marked by practical utilization, commercial value creation, and global public and private partnerships. While the ISS will not last forever, NASA has performed life extension analyses indicating the ISS can operate safely through 2030.[1] It is in the interest of the United States, and an opportunity for other free spacefaring nations, to create a smooth and seamless transition from the ISS to new commercial space stations. Per the US Space Priorities Framework,[2] our vision is also to continue human presence in low Earth orbit, leading toward expansion of free world enterprises. Our continued presence in space will create a growing expansion of the global economy that allows a space civilization where everyday people live, work, and thrive safely in space.

A critical step toward creation of this new earth-space econosphere is a gapless transition to commercial space stations. This transition must ensure that the US government and its current international ISS partners retain a seamless ability to continue using low Earth orbit platforms for space frontier research and expansion. Any gap could jeopardize the strong network of international partnerships and enterprises that have been in place over the last two decades and could halt their continuing maturation.[1]

The Russian threat

It is recognized that Russia has been a significant ISS partner working with the United States and other partner nations in developing and operating the ISS. But Roscosmos has completed its extension analyses only through 2024.[1] With recent political shifts it appears that no clarity on Russia’s ability to support ISS extension until 2030 will be forthcoming. This puts ISS operations, the US transition, and other partners’ plans in jeopardy. Further, over the last year, the Russian government and the head of the Russian space program have time and again threatened to unilaterally withdraw from the ISS.[3] Although in direct violation of their original partner agreements, Russia feels they can do this because their Progress transport modules currently provide the only means to keep the 500-ton station from crashing back to Earth anywhere between 52° north latitude and 52° south latitude.

To further complicate the state of these matters, the Russian-Ukrainian crisis this year saw the essential dissolution of the ISS partnership with Russia. On February 24, 2022, Dmitry Olegovich Rogozin, the director general of Roscosmos, threatened to prematurely abandon the International Space Station to die in an early, uncontrolled reentry.[4]. Such threats put in jeopardy the safety and livelihood of people in the countries under the ISS trajectory. A disaster of such an early and uncontrolled reentry also places NASA and other commercial space companies at the risk of losing the hard earned public, economic, and government headway toward future space exploration and commercial endeavors.

These withdrawal threats and Russian behavior provide clear indicators that it isn’t whether Russia will exit the ISS, but rather when. The United States and allied partner countries need to be ready to safeguard their people, interests, and the ISS itself from such a contingency. Ignoring or minimizing these facts will not make them go away.

More importantly, Russian actions show that we do not have the luxury of waiting to create responses and begin to transition the ISS to commercial partners.[1] The United States must act now to ensure that clear and actionable contingencies exist to ensure the safety of ISS operations through the transition period. Homer Hickam, a former NASA engineer and adviser to the National Space Council, has even recommended in a recent article[5] that Russian participation in the joint operation of the ISS should be reviewed by the National Space Council and with our international partners to determine whether Russia should continue to contribute to ISS operations.

Required actions

In response to these recent events and growing commercial space habitat market interest, two vital actions are needed from the United States government.

| Can space still hold the future for human expansion when faced with recent threats and hostility from Russia? Yes, if we move away from relying on the Russians and take needed actions to rely on ourselves and our trusted partners |

First, the administration should direct NASA to create a detailed review in the next 90 days that describes options for assuring the survival of ISS through the 2030 transition to commercial space facilities that shows the public all contingencies are covered. This contingency review needs to include plans that address technical options, space-environmental impacts, operational/logistical requirements, political and international cooperation considerations, and budgetary costs. It must include thoughtful considerations for safely operating through 2030 and decommissioning the ISS at the end of its life. A key part of this review is having NASA specify the technical requirements that allow industry to rapidly replace all the essential ISS functions provided by the Russian modules. It should study capabilities such as the creation of special docking adapters, procedures for exploiting deboost/reboost units like the Dragon, Cygnus, or other non-Russian propulsion systems. The review should also consider transition and decommissioning option reviews. These include the selective salvaging of still-useful ISS components (both government and commercial) and procedures for disassembly or deconstructing individual modules to provide greater disposal control and safety. Most importantly, contingencies need to be addressed and documented with a standard of quality and detail that citizens expect from NASA.

Once this ISS contingency review is completed, authorities such as the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP) should evaluate its adequacy and quality, and identify which plans and methods should be published for a 90-day public view and comment. Consequently, this allows other entities such as the administration, Congress, industry, and the public to confidently engage in prudent decisions regarding the plans and their scope and roles in supporting plan execution.

Second, the administration should support and direct NASA to aggressively coordinate with other agencies to remove bureaucratic barriers which could hamper new commercial space facility progress toward replacing the ISS with commercial space stations as stated in the ISS Transition Report.[1] The key objective of these actions is having NASA clearly specify their minimum service requirements. This will allow all industry players and stakeholders to be in a position to confidently create space facility market capabilities for NASA and also that are attractive for commercial customers. Working with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and congressional committees, the administration can work to fast-track the authorization of necessary and sufficient budgets to mitigate Russian threats while catalyzing commercial investments for a continuing commercial space facilities market.

The fundamental question is, can space still hold the future for human expansion when faced with recent threats and hostility from Russia? Yes, if we move away from relying on the Russians and take needed actions to rely on ourselves and our trusted partners. This can be done by addressing the contingencies quickly and charting a clear ISS transition course of action by fully supporting the commercial space station entrants. Frank collaboration with our international partners safeguarding the ISS through transition and decommissioning is also required.

The threat of early termination of the ISS is a crisis and we must treat it as such. Future generations will hold us accountable in our responses to this challenge of transitioning to a prosperous space frontier. As John F. Kennedy said, “There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind.” It is imperative that we act now to mitigate all possibilities of Russian non-participation in the ISS.

References

- NASA, “International Space Station Transition Report”, January 2022.

- White House, “United States Space Priorities Franework”, December 2021.

- CNBC, “Russia’s space chief threatens to leave International Space Station program unless U.S. lifts sanctions”, June 7, 2021.

- The Space Review, “The ending of an era in international space cooperation”, February 28, 2022.

- Washington Post, “Our space partnership with Russia can’t go on”, March 9, 2022.

Srikanth Raviprasad is an aerospace engineer who leads multiple aircraft programs in the business jet industry and volunteers with leading nonprofit organizations for the sustainable exploration and development of the final frontier and enjoys engaging with the community to learn, share ideas and knowledge about space. Steve Hoeser is a senior space systems engineer, former space systems project lead and former chief space systems architect.

The views, ideas, and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of their employers.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

What If Aliens From Another Planet Arrived On Earth With Sinister Intentions?

A subject near and dear to my heart always is intelligent life on other planets. I believe that such life does exist throughout our galaxy and other galaxies. We are pretty safe from visits by these other intelligent societies due to the tyranny of distance and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity which sets the maximum possible speed at the speed of light (186,000 miles per second.)

What if some aliens did arrive on our planet and their intentions were sinister? A brilliant television show has explored this possibility. It is a French and British production titled “War of the Worlds.” You can find it on Amazon Prime videos. If you speak French, you will love it even more. Here is the link:

NASA Sending A Message To The Milky Way

You’ve Got Mail

NASA scientists are planning to beam a new message across the Milky Way galaxy in the hope of making contact with intelligent extraterrestrial beings, the Guardian reported.

The “Beacon in the Galaxy” will include simple principles of communication, a few basic concepts about mathematics and physics, as well as a history of Earth and humanity. The research team has also placed a return address in case there is a reply.

“Humanity has … a compelling story to share and the desire to know of others – and now has the means to do so,” the team wrote in their paper.

Lead author Jonathan Jiang said the message will be delivered to a dense ring of stars near the center of the Milky Way, a region believed to have the biggest potential for life to have emerged.

Still, a lot of questions linger about the move, such as whether the message will ever be picked up and if the recipients will understand it. And if they do, when – and how – they will reply.

The late scientist Stephen Hawking had posited the dangers of such an endeavor and compared it to Christopher Columbus’ arrival in America.

“(It) didn’t turn out well for the Native Americans,” he told a Discovery channel documentary.

But Jiang and other researchers are looking at the bright side, suggesting that humanity “could have much to learn” from others in the universe.

The beacon is not the first human attempt at interstellar communication.

In 1974, scientists sent out the Arecibo message toward a cluster of stars about 25,000 light-years away. It won’t arrive any time soon.