| |  Nichelle Nichols is shown in NASA’s Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center in March 1977. (credit: NASA)Chief communicator: How Star Trek’s Lieutenant Uhura helped NASAby Glen E. Swanson Nichelle Nichols is shown in NASA’s Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center in March 1977. (credit: NASA)Chief communicator: How Star Trek’s Lieutenant Uhura helped NASAby Glen E. Swanson

Monday, August 15, 2022

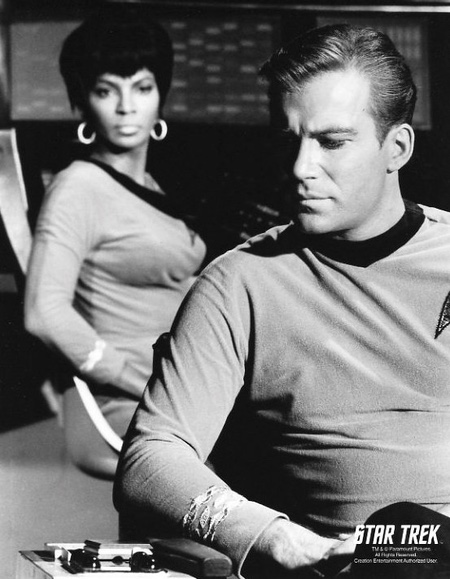

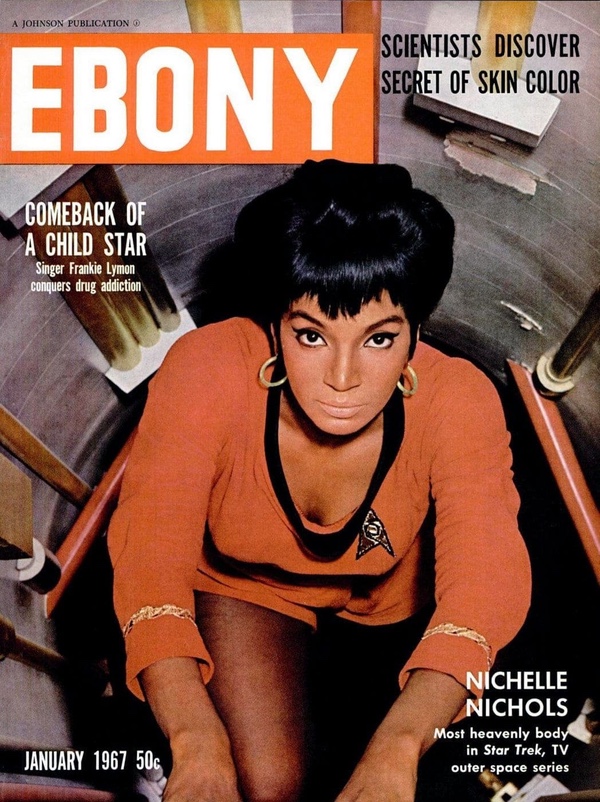

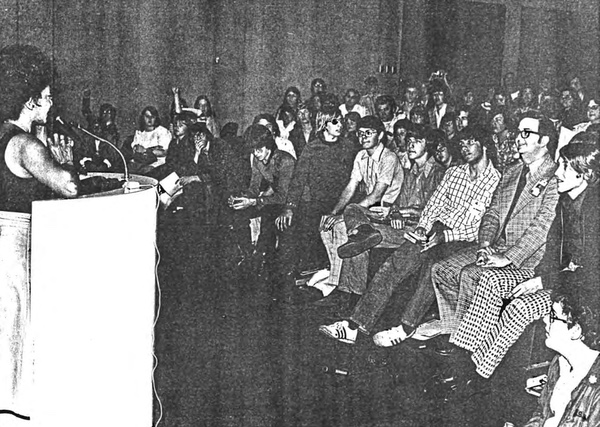

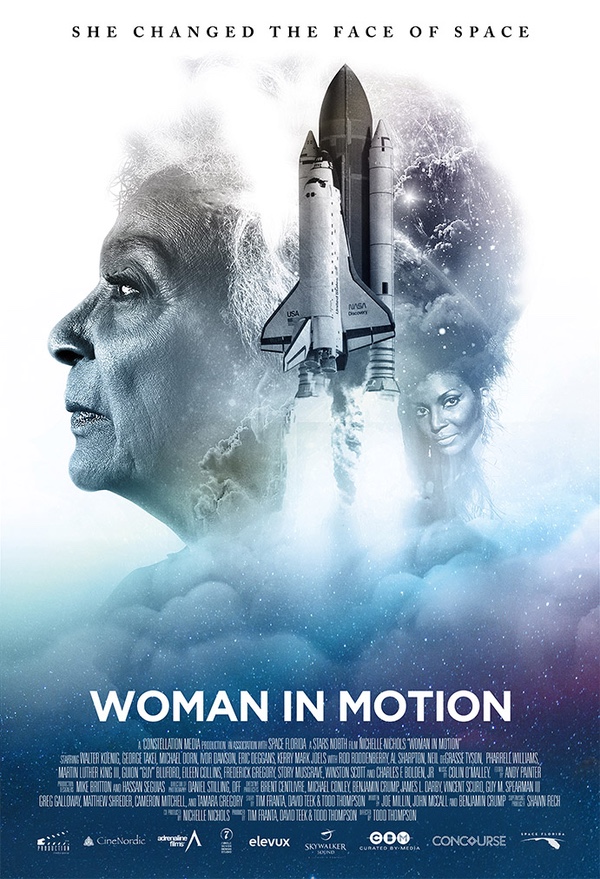

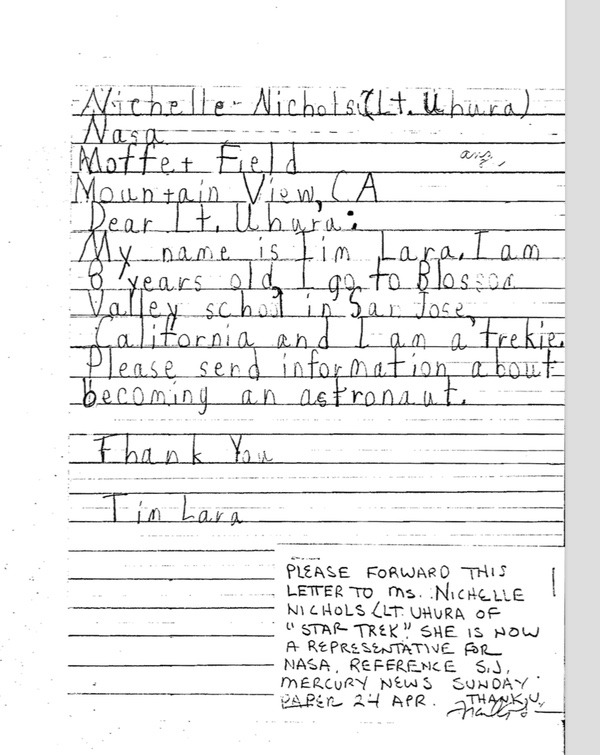

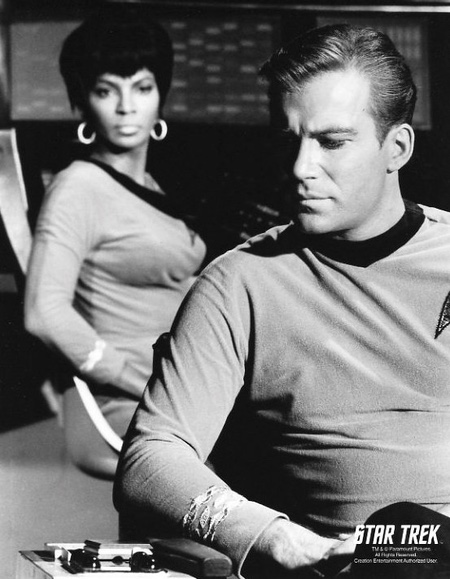

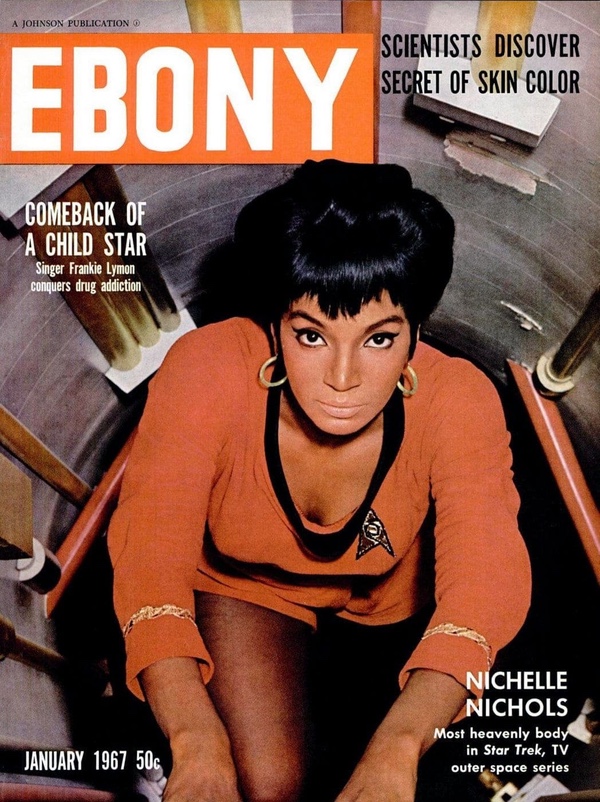

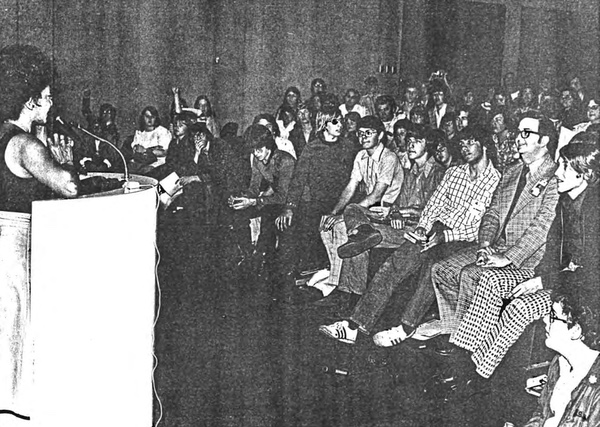

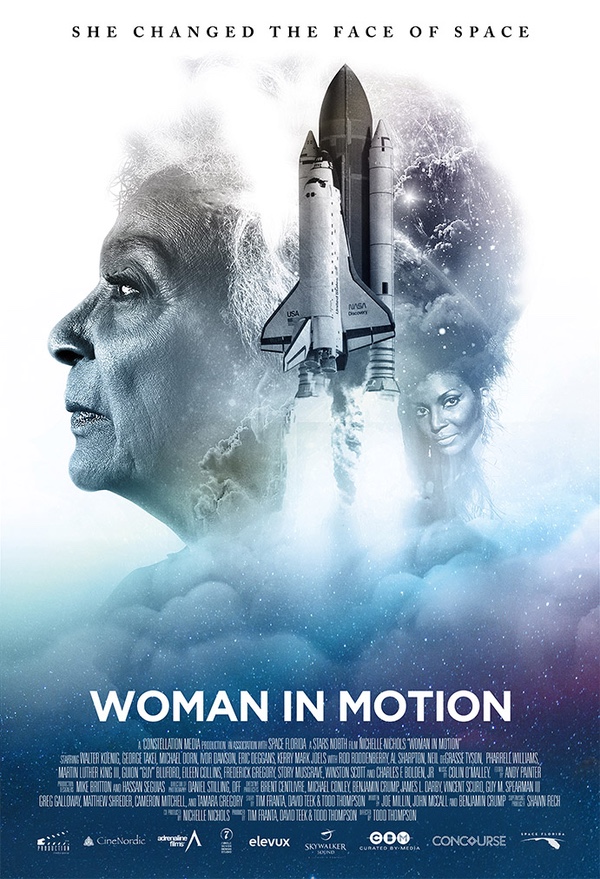

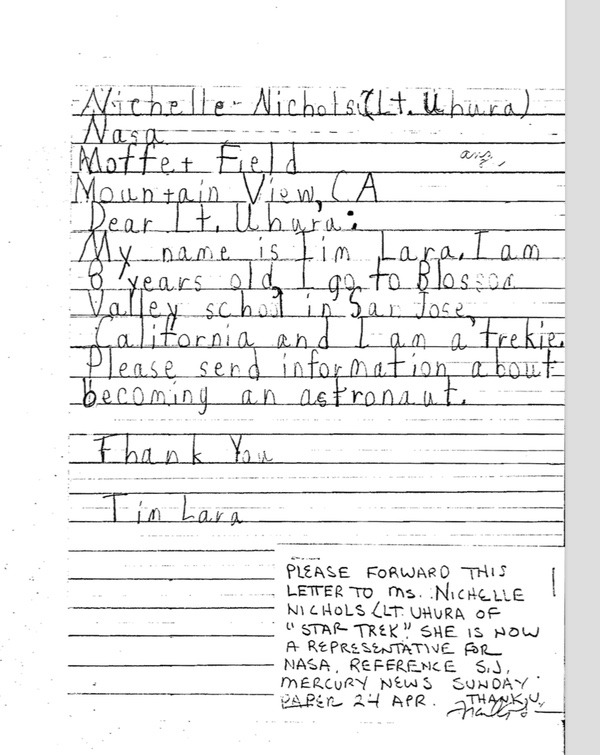

With the recent death of Nichelle Nichols, the number of surviving principal cast members of Gene Roddenberry’s original Star Trek television series shrank again. There now remain only three regular crew members of the Starship Enterprise: Ensign Chekov (Walter Koenig), Lieutenant Sulu (George Takei) and Captain Kirk (William Shatner) to help remind us of the pioneering television series that originally aired on NBC from 1966 to 1969.Nichelle Nichols’ down-to-earth work with NASA is often overshadowed by her role on Star Trek. This essay attempts to focus not so much on Nichols’ television role but on her work with NASA and the larger space community that she later associated with after leaving the series in 1969. This article will show that Nichols was not just a celebrity doing celebrity things but was also employed as a contractor by NASA to help with the space agency’s goal of bringing more attention to itself along with more diversity to its workforce.Star Trek broke new ground in many areas, not the least of which was having a diversity of both human (and alien) races serving as lead characters during a time when television audiences were not accustomed to seeing a serious science fiction series, especially one depicting a strong Black female. Publicity photo of Nichelle Nichols and William Shatner. (credit: Paramount/CBS)Outfitted in a bright red miniskirt uniform during a time when black and white TVs were being phased out by color sets (at the time of Star Trek, NBC was owned by RCA, a leading color television manufacturer, and advertising for the network often featured RCA sets), Nichelle Nichols’ character of Lieutenant Uhura stood out not only because she was Black but also because showrunner Gene Rodenberry believed that various races and ethnicities would be well represented in the future. Her workstation aboard the ship’s bridge was located close to the Captain’s chair and next to the ship’s second-in-command, the pointed-eared half-human, half-Vulcan Mr. Spock. The talented actress was regularly shown on screen during many of the show’s deciding moments. But even though she was seen as the ship’s chief communications officer, she was often not heard, a fact that did not go unnoticed by the actress herself.All the other characters in the show except Kirk, Spock, and McCoy, tended to be viewed as movable furniture. Nichols openly expressed frustration about her place in Star Trek, as her role was mostly limited to saying just three words “hailing frequencies open.” She told one interviewer, “She’s the chief communication officer and she can’t talk? What good is she?”[1]After listening to NASA’s Jesco von Puttkamer, Nichols began thinking about spaceflight—not the spaceflight of the 23rd century, but that of her own timeEven though she played a fictional character from a future where, presumably, people have moved beyond bigotry and racism, she had to live during a time when all of that was still very much real. Nichols told an interviewer, “The thing in 1966 was that everyone was scared to death of having a Black and a woman in an equal role. They [NBC executives] had just gotten through having a battle with Gene Roddenberry over Majel Barrett [who played Number One in the original pilot and Nurse Chapel in the series] in a strong female role, and they were scared to death of the South.”[2] After viewing the show’s first pilot episode, “The Cage,” NBC told Roddenberry that he could not have both the pointed-eared Vulcan Mr. Spock and the ship’s second in command played by Majel Barrett. Roddenberry let go of Number One but insisted on keeping Mr. Spock. After NBC saw a second pilot episode, Roddenberry was given the green light to proceed, and the rest is television history. Publicity photo of Nichelle Nichols and William Shatner. (credit: Paramount/CBS)Outfitted in a bright red miniskirt uniform during a time when black and white TVs were being phased out by color sets (at the time of Star Trek, NBC was owned by RCA, a leading color television manufacturer, and advertising for the network often featured RCA sets), Nichelle Nichols’ character of Lieutenant Uhura stood out not only because she was Black but also because showrunner Gene Rodenberry believed that various races and ethnicities would be well represented in the future. Her workstation aboard the ship’s bridge was located close to the Captain’s chair and next to the ship’s second-in-command, the pointed-eared half-human, half-Vulcan Mr. Spock. The talented actress was regularly shown on screen during many of the show’s deciding moments. But even though she was seen as the ship’s chief communications officer, she was often not heard, a fact that did not go unnoticed by the actress herself.All the other characters in the show except Kirk, Spock, and McCoy, tended to be viewed as movable furniture. Nichols openly expressed frustration about her place in Star Trek, as her role was mostly limited to saying just three words “hailing frequencies open.” She told one interviewer, “She’s the chief communication officer and she can’t talk? What good is she?”[1]After listening to NASA’s Jesco von Puttkamer, Nichols began thinking about spaceflight—not the spaceflight of the 23rd century, but that of her own timeEven though she played a fictional character from a future where, presumably, people have moved beyond bigotry and racism, she had to live during a time when all of that was still very much real. Nichols told an interviewer, “The thing in 1966 was that everyone was scared to death of having a Black and a woman in an equal role. They [NBC executives] had just gotten through having a battle with Gene Roddenberry over Majel Barrett [who played Number One in the original pilot and Nurse Chapel in the series] in a strong female role, and they were scared to death of the South.”[2] After viewing the show’s first pilot episode, “The Cage,” NBC told Roddenberry that he could not have both the pointed-eared Vulcan Mr. Spock and the ship’s second in command played by Majel Barrett. Roddenberry let go of Number One but insisted on keeping Mr. Spock. After NBC saw a second pilot episode, Roddenberry was given the green light to proceed, and the rest is television history. Ebony January 1967NASA takes noticeIn the January 1967 issue of Ebony magazine, Nichols appeared in a cover story that both labeled the actress as the “most heavenly body in Star Trek” and declared her to be “the first Negro astronaut, a triumph of modern-day TV over modern-day NASA.”[3] Nichols became a powerful advocate for the continued human exploration of space. She brought attention to the topic while at the same time speaking about her role as Uhura at Star Trek conventions. These events drew thousands of fans many of whom were initially too young to watch Star Trek during its original airing in the 1960s, but who became devoted followers of the show while watching the show in syndication.It was during one of these conventions, in her hometown of Chicago in 1975, where she along with over 30,000 attendees heard a talk by Jesco von Puttkamer, a NASA scientist and engineer. After listening to Puttkamer, Nichols began thinking about spaceflight—not the spaceflight of the 23rd century, but that of her own time. “I sat through Dr. von Puttkamer’s presentation in awe. I admit that until then I had not been fully aware of exactly what our national space program was about. Listening to Dr. von Puttkamer was a revelation to me. He put the space program in perspective and opened my eyes to its purpose and promise.”[4] Ebony January 1967NASA takes noticeIn the January 1967 issue of Ebony magazine, Nichols appeared in a cover story that both labeled the actress as the “most heavenly body in Star Trek” and declared her to be “the first Negro astronaut, a triumph of modern-day TV over modern-day NASA.”[3] Nichols became a powerful advocate for the continued human exploration of space. She brought attention to the topic while at the same time speaking about her role as Uhura at Star Trek conventions. These events drew thousands of fans many of whom were initially too young to watch Star Trek during its original airing in the 1960s, but who became devoted followers of the show while watching the show in syndication.It was during one of these conventions, in her hometown of Chicago in 1975, where she along with over 30,000 attendees heard a talk by Jesco von Puttkamer, a NASA scientist and engineer. After listening to Puttkamer, Nichols began thinking about spaceflight—not the spaceflight of the 23rd century, but that of her own time. “I sat through Dr. von Puttkamer’s presentation in awe. I admit that until then I had not been fully aware of exactly what our national space program was about. Listening to Dr. von Puttkamer was a revelation to me. He put the space program in perspective and opened my eyes to its purpose and promise.”[4] The rollout of the first Space Shuttle OV-101 Enterprise occurred on September 17, 1976 at Rockwell International’s Palmdale, California, facility. As the orbiter emerged from the hangar, the Air Force Band of the Golden West from March Air Force Base in Riverside, California, played Alexander Courage’s main theme to Star Trek. Shown left to right is NASA Administrator James Fletcher along with Star Trek principal cast members DeForest Kelley, George Takei, Nichelle Nichols, Leonard Nimoy and series creator Gene Roddenberry. Carl Sagan, famed astronomer and creator of the PBS series Cosmos, can also be seen between Fletcher’s and Kelley’s shoulders. (credit: NASA)While touring various NASA field centers, colleges and universities, Nichols’ appearances became more focused on space advocacy. On July 20, 1976, she was invited to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to witness the landing of the first Viking mission to Mars and, in September, she, along with most of the cast from the original television series, attended the Palmdale, California, rollout of the first space shuttle orbiter. President Ford had named the world’s first reusable spacecraft Enterprise, which many Star Trek fans supported by engaging in an earlier letter writing campaign that encouraged the President to change it to that from Constitution. The rollout of the first Space Shuttle OV-101 Enterprise occurred on September 17, 1976 at Rockwell International’s Palmdale, California, facility. As the orbiter emerged from the hangar, the Air Force Band of the Golden West from March Air Force Base in Riverside, California, played Alexander Courage’s main theme to Star Trek. Shown left to right is NASA Administrator James Fletcher along with Star Trek principal cast members DeForest Kelley, George Takei, Nichelle Nichols, Leonard Nimoy and series creator Gene Roddenberry. Carl Sagan, famed astronomer and creator of the PBS series Cosmos, can also be seen between Fletcher’s and Kelley’s shoulders. (credit: NASA)While touring various NASA field centers, colleges and universities, Nichols’ appearances became more focused on space advocacy. On July 20, 1976, she was invited to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to witness the landing of the first Viking mission to Mars and, in September, she, along with most of the cast from the original television series, attended the Palmdale, California, rollout of the first space shuttle orbiter. President Ford had named the world’s first reusable spacecraft Enterprise, which many Star Trek fans supported by engaging in an earlier letter writing campaign that encouraged the President to change it to that from Constitution. Nichelle Nichols and Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California in July 1976 during the Viking 1 landing on Mars. (credit: Don Davis)Because of her growing popularity as a space popularizer, in 1976 Nichols, along with Shirley Bryant Keith, Shannon O’Brien and Janet Holbrook, formed a company called “Women in Motion.”[5] The stated purpose of the company was “to produce educational and motivational films for minority youth; to encourage them to consider careers in the fields of engineering and science and to prepare them for the rapidly developing technology of the future.”[6]In January 1977, Nichols was elected to the board of directors of the newly formed National Space Institute (which later became the National Space Society), a civilian space advocacy group founded by famed rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun. Shortly after being elected, Nichols gave a speech to the NSI council meeting in Washington titled “New Opportunities for the Humanization of Space.” In her speech she challenged “NASA and everyone else involved in the space program to answer the question I’d heard a thousand times in my travels: ‘Space? So what’s in it for me?’”[7] Those in attendance during her speech included Dr. James Fletcher, the administrator of NASA.In her speech she challenged “NASA and everyone else involved in the space program to answer the question I’d heard a thousand times in my travels: ‘Space? So what’s in it for me?’”Fletcher was impressed by what he heard in Nichols. At the time, NASA sought to recruit more engineers and astronauts into its new Space Shuttle program and to attract more women and racial minorities. In addition, NASA introduced two new categories of astronauts—mission specialist and payload specialist—who would be researchers first and pilots second. The space agency’s requirement that all astronauts have military test pilot experience was dropped in the mid 1960s, thereby allowing the first group of scientist-astronauts to be chosen in 1965. This group of six scientist-astronauts made up NASA’s Group 4 batch of astronauts. Now, 12 years later, NASA wanted women to apply to become astronauts in the new Group 8 selection.By February 1977, after eight months of promoting the program, NASA received 1,500 astronaut applications and of those submitted approximately 30 were identifiable as minorities and 75 identifiable as women. With the deadline for applicants to file for the next astronaut group closing on June 30 of that same year, NASA was looking to further expand its selection pool. Nichols wrote that NASA was “perceiving a necessity for the human development of minorities in mathematics, science and engineering and the need for the encouragement of the broad participation of minorities and women in the space program.”[8] As a result, NASA awarded contract NASW-3049 to her Women in Motion Production Company specifically, “to embark on a review of NASA recruitment activities and a concerted effort to inform minorities and women of the opportunities available in the program and to encourage their active participation.” The $49,900 contract began on February 10 and ended six months later on August 10, 1977.[9] Nichelle Nichols and Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California in July 1976 during the Viking 1 landing on Mars. (credit: Don Davis)Because of her growing popularity as a space popularizer, in 1976 Nichols, along with Shirley Bryant Keith, Shannon O’Brien and Janet Holbrook, formed a company called “Women in Motion.”[5] The stated purpose of the company was “to produce educational and motivational films for minority youth; to encourage them to consider careers in the fields of engineering and science and to prepare them for the rapidly developing technology of the future.”[6]In January 1977, Nichols was elected to the board of directors of the newly formed National Space Institute (which later became the National Space Society), a civilian space advocacy group founded by famed rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun. Shortly after being elected, Nichols gave a speech to the NSI council meeting in Washington titled “New Opportunities for the Humanization of Space.” In her speech she challenged “NASA and everyone else involved in the space program to answer the question I’d heard a thousand times in my travels: ‘Space? So what’s in it for me?’”[7] Those in attendance during her speech included Dr. James Fletcher, the administrator of NASA.In her speech she challenged “NASA and everyone else involved in the space program to answer the question I’d heard a thousand times in my travels: ‘Space? So what’s in it for me?’”Fletcher was impressed by what he heard in Nichols. At the time, NASA sought to recruit more engineers and astronauts into its new Space Shuttle program and to attract more women and racial minorities. In addition, NASA introduced two new categories of astronauts—mission specialist and payload specialist—who would be researchers first and pilots second. The space agency’s requirement that all astronauts have military test pilot experience was dropped in the mid 1960s, thereby allowing the first group of scientist-astronauts to be chosen in 1965. This group of six scientist-astronauts made up NASA’s Group 4 batch of astronauts. Now, 12 years later, NASA wanted women to apply to become astronauts in the new Group 8 selection.By February 1977, after eight months of promoting the program, NASA received 1,500 astronaut applications and of those submitted approximately 30 were identifiable as minorities and 75 identifiable as women. With the deadline for applicants to file for the next astronaut group closing on June 30 of that same year, NASA was looking to further expand its selection pool. Nichols wrote that NASA was “perceiving a necessity for the human development of minorities in mathematics, science and engineering and the need for the encouragement of the broad participation of minorities and women in the space program.”[8] As a result, NASA awarded contract NASW-3049 to her Women in Motion Production Company specifically, “to embark on a review of NASA recruitment activities and a concerted effort to inform minorities and women of the opportunities available in the program and to encourage their active participation.” The $49,900 contract began on February 10 and ended six months later on August 10, 1977.[9] In March 1977 one of the first stops by Nichelle Nichols as part of her new NASA contract was at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. There she toured the facilities and met with astronauts including Alan Bean, the fourth man to walk on the Moon. (credit: NASA)Warp speed aheadWith the ink barely dried on her new NASA contract, one of the first stops that Nichols made was to Houston, Texas, where NASA’s astronauts lived and worked. There she met with various officials and astronauts at NASA’s Johnson Space Center to talk about her recruitment campaign. It was here that she met astronaut Alan Bean, who was the fourth man to walk on the surface of the Moon during Apollo 12. Bean met with Nichols in March 1977 and was her host during her visit, appearing with her in simulation and training exercises that were filmed on the space center’s grounds and made into a video to help Nichols recruit minorities and women to work for NASA and to apply in the astronaut program.Bean was also a talented painter who captured his space flight experiences on canvas. NASA chose Bean to work with Nichols not only because of his experience as an astronaut and moonwalker, but like Nichols, he was also an artist who most likely felt comfortable working with another talented artist like Nichols. Bean retired from the Navy in October 1975 but continued as head of the Astronaut Candidate Operations and Training Group within the Astronaut Office in a civilian capacity until his retirement from NASA in 1981. In March 1977 one of the first stops by Nichelle Nichols as part of her new NASA contract was at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. There she toured the facilities and met with astronauts including Alan Bean, the fourth man to walk on the Moon. (credit: NASA)Warp speed aheadWith the ink barely dried on her new NASA contract, one of the first stops that Nichols made was to Houston, Texas, where NASA’s astronauts lived and worked. There she met with various officials and astronauts at NASA’s Johnson Space Center to talk about her recruitment campaign. It was here that she met astronaut Alan Bean, who was the fourth man to walk on the surface of the Moon during Apollo 12. Bean met with Nichols in March 1977 and was her host during her visit, appearing with her in simulation and training exercises that were filmed on the space center’s grounds and made into a video to help Nichols recruit minorities and women to work for NASA and to apply in the astronaut program.Bean was also a talented painter who captured his space flight experiences on canvas. NASA chose Bean to work with Nichols not only because of his experience as an astronaut and moonwalker, but like Nichols, he was also an artist who most likely felt comfortable working with another talented artist like Nichols. Bean retired from the Navy in October 1975 but continued as head of the Astronaut Candidate Operations and Training Group within the Astronaut Office in a civilian capacity until his retirement from NASA in 1981. Nichelle Nichols at the NASA Johnson Space Center in March 1977. (credit: NASA)During this same time at JSC, Nichols addressed more than 2,000 students from Texas junior and senior high schools that attend “NASA Symposium ’77” hosted at the Space Center. This was a first-of-its-kind event for NASA designed to motivate youth, especially female and minority students, to seek careers in engineering and science.[10] Nichelle Nichols at the NASA Johnson Space Center in March 1977. (credit: NASA)During this same time at JSC, Nichols addressed more than 2,000 students from Texas junior and senior high schools that attend “NASA Symposium ’77” hosted at the Space Center. This was a first-of-its-kind event for NASA designed to motivate youth, especially female and minority students, to seek careers in engineering and science.[10] During her visit to the NASA Johnson Space Center Nichelle Nichols addressed more than 2,000 students from Texas junior and senior high schools who attend “NASA Symposium ’77” hosted by the Space Center. (credit: NASA)With contract in hand, Nichols left JSC to continue her cross-country public relations campaign for NASA. The final report that her company submitted at the close of the contract shows a very aggressive schedule. Even though the contract was for six months, the focus of her PR campaign was during a four-month period and it was grueling. Nichols cancelled all previous engagements and literally put her life on hold to engage in a cause that she felt was truly important. During her visit to the NASA Johnson Space Center Nichelle Nichols addressed more than 2,000 students from Texas junior and senior high schools who attend “NASA Symposium ’77” hosted by the Space Center. (credit: NASA)With contract in hand, Nichols left JSC to continue her cross-country public relations campaign for NASA. The final report that her company submitted at the close of the contract shows a very aggressive schedule. Even though the contract was for six months, the focus of her PR campaign was during a four-month period and it was grueling. Nichols cancelled all previous engagements and literally put her life on hold to engage in a cause that she felt was truly important. Nichelle Nichols visiting the NASA Kennedy Space Center in 1977. (credit: NASA)“I went to every university that I could get to. I went to every woman’s organization, every professional science organization, the organization of Black engineers, I went to the Asian community, I went to the Spanish-American community, I went to the organization of Black pilots. Fortunately many of these people were having their annual conventions at that time. And many admitted that they allowed me to come because I was Uhura but they finished up because I was Nichelle Nichols speaking for our space program.”[11] Nichelle Nichols visiting the NASA Kennedy Space Center in 1977. (credit: NASA)“I went to every university that I could get to. I went to every woman’s organization, every professional science organization, the organization of Black engineers, I went to the Asian community, I went to the Spanish-American community, I went to the organization of Black pilots. Fortunately many of these people were having their annual conventions at that time. And many admitted that they allowed me to come because I was Uhura but they finished up because I was Nichelle Nichols speaking for our space program.”[11] NASA Dryden (now Armstrong) Center Director Isaac “Ike” Gillam with Nichelle Nichols in 1977. (credit: NASA)During the summer of 1977, Nichols traveled across the country, recruiting folks to come and work for NASA. Several weeks prior to the June 30 NASA astronaut application deadline, Nichols filmed a television segment for the popular ABC morning television news show Good Morning America. That segment aired on June 14 and showed Nichols on the campus of NASA’s Johnson Space Center talking about her work with shuttle astronaut Bill Pogue, who flew on Skylab 3. This major news network spot greatly increased interest among the public about what Nichols was doing and her efforts to recruit people to work for NASA. NASA Dryden (now Armstrong) Center Director Isaac “Ike” Gillam with Nichelle Nichols in 1977. (credit: NASA)During the summer of 1977, Nichols traveled across the country, recruiting folks to come and work for NASA. Several weeks prior to the June 30 NASA astronaut application deadline, Nichols filmed a television segment for the popular ABC morning television news show Good Morning America. That segment aired on June 14 and showed Nichols on the campus of NASA’s Johnson Space Center talking about her work with shuttle astronaut Bill Pogue, who flew on Skylab 3. This major news network spot greatly increased interest among the public about what Nichols was doing and her efforts to recruit people to work for NASA. In June 1977 Nichols visited the NASA Johnson Space Center to film a morning segment for the popular ABC program Good Morning America. There she spoke with astronaut Bill Pogue. (credit: ABC)In her report she found that the reason there were so few NASA applications from minorities and women was “because of open hostility, disbelief, gross misinformation and apathy toward NASA.”At the same time that Nichols was promoting NASA, the public was being swept away by the space spectacular known as Star Wars. Millions saw Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, Obi Wan Kenobi, and Princess Leia do battle on the big screen that summer against the villainous Darth Vader. Nichols was courting that same audience, leveraging her own famous science fiction character in order to show how fans themselves could apply to actually work in space. The popularity of George Lucas’ film that summer did not hurt her efforts to engage the interest of the general public about possible careers with NASA.At the close of her contract, Nichols submitted a report. In her report she found that the reason there were so few NASA applications from minorities and women was “because of open hostility, disbelief, gross misinformation and apathy toward NASA.” There were a lot of “feelings of hurt among women who genuinely wanted to be astronauts, and among minorities, who felt heretofore left out if not deliberately excluded.”[12] Another of her observations resulted from several prior commitments that Nichols made outside of her NASA contractual obligations. These involved attending several NASA symposia and Star Trek conventions where Nichols wrote:“She [Nichelle Nichols] appeared before approximately 50,000 people at major science-fiction conventions such as those in San Francisco… Her public was at first dismayed as they had not perceived ‘their’ Lt. Uhura (Ms. Nichols character in the television series Star Trek) as becoming absorbed in real time space activities such as NASA’s efforts to recruit minorities and women. As Ms. Nichols’ extensive media coverage pervaded the country, she evolved a positive response from the public, and thus these occasions became opportunities. Questions directed to Ms. Nichols shifted from interest in her celebrity status as a fictional character to serious topics related to space exploration and space development, and her personal appearances now became anxiously awaited ‘Report to the fans’ on Ms. Nichols’ progress in recruiting minorities and women to participate in the real space exploration of today. Credibility, along with fervent commitment of NASA’s space program, became established fact.”[13]When Nichols spoke, she was sometimes confronted by claims that NASA was using her. She replied, “I know. And I’m using NASA too. But if you don’t apply, then they are right. If you qualify and you really wanted to [apply] and you don’t apply, they are right.”[14]By the end of June 1977, Nichols reported some 8,000 applicants were received by NASA’s astronaut office. Of this number she wrote, “1,649 were from women and over 1,000 were from minorities.” Among the applicants were Sally Ride, the first American woman to go into space; Fred Gregory and Guy Bluford, two of the first African-American astronauts, as well as three astronauts who later died in the 1986 Challenger accident: Judith Resnik, Ronald McNair, and Ellison Onizuka. Nichols efforts produced results that not only helped NASA diversify its overall workforce but also that of its new astronaut class of 1978. These “Thirty-Five New Guys” comprised “Selection Group 8,” the first new astronaut candidates to include Black people and women.[15,16] In June 1977 Nichols visited the NASA Johnson Space Center to film a morning segment for the popular ABC program Good Morning America. There she spoke with astronaut Bill Pogue. (credit: ABC)In her report she found that the reason there were so few NASA applications from minorities and women was “because of open hostility, disbelief, gross misinformation and apathy toward NASA.”At the same time that Nichols was promoting NASA, the public was being swept away by the space spectacular known as Star Wars. Millions saw Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, Obi Wan Kenobi, and Princess Leia do battle on the big screen that summer against the villainous Darth Vader. Nichols was courting that same audience, leveraging her own famous science fiction character in order to show how fans themselves could apply to actually work in space. The popularity of George Lucas’ film that summer did not hurt her efforts to engage the interest of the general public about possible careers with NASA.At the close of her contract, Nichols submitted a report. In her report she found that the reason there were so few NASA applications from minorities and women was “because of open hostility, disbelief, gross misinformation and apathy toward NASA.” There were a lot of “feelings of hurt among women who genuinely wanted to be astronauts, and among minorities, who felt heretofore left out if not deliberately excluded.”[12] Another of her observations resulted from several prior commitments that Nichols made outside of her NASA contractual obligations. These involved attending several NASA symposia and Star Trek conventions where Nichols wrote:“She [Nichelle Nichols] appeared before approximately 50,000 people at major science-fiction conventions such as those in San Francisco… Her public was at first dismayed as they had not perceived ‘their’ Lt. Uhura (Ms. Nichols character in the television series Star Trek) as becoming absorbed in real time space activities such as NASA’s efforts to recruit minorities and women. As Ms. Nichols’ extensive media coverage pervaded the country, she evolved a positive response from the public, and thus these occasions became opportunities. Questions directed to Ms. Nichols shifted from interest in her celebrity status as a fictional character to serious topics related to space exploration and space development, and her personal appearances now became anxiously awaited ‘Report to the fans’ on Ms. Nichols’ progress in recruiting minorities and women to participate in the real space exploration of today. Credibility, along with fervent commitment of NASA’s space program, became established fact.”[13]When Nichols spoke, she was sometimes confronted by claims that NASA was using her. She replied, “I know. And I’m using NASA too. But if you don’t apply, then they are right. If you qualify and you really wanted to [apply] and you don’t apply, they are right.”[14]By the end of June 1977, Nichols reported some 8,000 applicants were received by NASA’s astronaut office. Of this number she wrote, “1,649 were from women and over 1,000 were from minorities.” Among the applicants were Sally Ride, the first American woman to go into space; Fred Gregory and Guy Bluford, two of the first African-American astronauts, as well as three astronauts who later died in the 1986 Challenger accident: Judith Resnik, Ronald McNair, and Ellison Onizuka. Nichols efforts produced results that not only helped NASA diversify its overall workforce but also that of its new astronaut class of 1978. These “Thirty-Five New Guys” comprised “Selection Group 8,” the first new astronaut candidates to include Black people and women.[15,16] While principal filming for Star Trek: The Motion Picture was underway in early 1978, Uhura managed to sneak away from the set in her communications officer’s uniform to do a short film for the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum called Space: What’s In It for Me?. (credit: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum)The adventure continues…Nichols involvement with NASA and the general space community did not end at the close of her contract. Because of the phenomenal success of Star Wars, Hollywood studios began dusting off their holdings to see how they could cash in on the new craze for science fiction films. Paramount Pictures held the rights to Star Trek and after several false starts, produced a major studio film that reunited Uhura with all of the major cast members from the original series for the very first time on the big screen. Although it did not gross as much as Star Wars, Star Trek: The Motion Picture was a success at the box office when it premiered in December 1979.While principal filming for Star Trek: The Motion Picture was underway in early 1978, Uhura managed to sneak away from the set in her new communications officer’s uniform to do a short film for the Smithsonian. Dr. Kerry Joels, then director of education for the National Air and Space Museum, suggested that Nichols create a short orientation film to try and attract young people, especially girls, minorities and the underserved, to the new museum building that had opened on the National Mall just two years earlier. Nichols’ Women in Motion took on the task and filmed a group of non-professional kids from DC area schools who were depicted as an English class undertaking a field trip to the museum. Among them was a little girl named Lishia. In the story depicted by the film, the teacher, who was played by a real-life teacher, had given each student a different assignment and Lishia’s task was to distinguish the differences between space fact and space fantasy. When Lishia encounters the original 11-foot production model Enterprise that was used in the filming of the original series, Uhura beams down to the museum. Lishia acts as a docent, guiding Uhura through the museum while they talk about space. Uhura sings a song called “Reach for Your Star,” one of two songs that she and her husband Jim wrote for the film. Uhura soon realizes that the rest of the class will be coming so she quickly asks Scotty to beam her back. After doing so, all that is left of Uhura for Lishia are the memories of the event and Uhura’s earpiece left on the floor. As Lishia holds the small earpiece she hears Uhura singing “Remember, Lishia, always reach for your star…” The 20-minute film called Space: What’s in It for Me? was shown at the Air and Space Museum for a year.[17] Recently, NASM posted select portions from that film. While principal filming for Star Trek: The Motion Picture was underway in early 1978, Uhura managed to sneak away from the set in her communications officer’s uniform to do a short film for the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum called Space: What’s In It for Me?. (credit: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum)The adventure continues…Nichols involvement with NASA and the general space community did not end at the close of her contract. Because of the phenomenal success of Star Wars, Hollywood studios began dusting off their holdings to see how they could cash in on the new craze for science fiction films. Paramount Pictures held the rights to Star Trek and after several false starts, produced a major studio film that reunited Uhura with all of the major cast members from the original series for the very first time on the big screen. Although it did not gross as much as Star Wars, Star Trek: The Motion Picture was a success at the box office when it premiered in December 1979.While principal filming for Star Trek: The Motion Picture was underway in early 1978, Uhura managed to sneak away from the set in her new communications officer’s uniform to do a short film for the Smithsonian. Dr. Kerry Joels, then director of education for the National Air and Space Museum, suggested that Nichols create a short orientation film to try and attract young people, especially girls, minorities and the underserved, to the new museum building that had opened on the National Mall just two years earlier. Nichols’ Women in Motion took on the task and filmed a group of non-professional kids from DC area schools who were depicted as an English class undertaking a field trip to the museum. Among them was a little girl named Lishia. In the story depicted by the film, the teacher, who was played by a real-life teacher, had given each student a different assignment and Lishia’s task was to distinguish the differences between space fact and space fantasy. When Lishia encounters the original 11-foot production model Enterprise that was used in the filming of the original series, Uhura beams down to the museum. Lishia acts as a docent, guiding Uhura through the museum while they talk about space. Uhura sings a song called “Reach for Your Star,” one of two songs that she and her husband Jim wrote for the film. Uhura soon realizes that the rest of the class will be coming so she quickly asks Scotty to beam her back. After doing so, all that is left of Uhura for Lishia are the memories of the event and Uhura’s earpiece left on the floor. As Lishia holds the small earpiece she hears Uhura singing “Remember, Lishia, always reach for your star…” The 20-minute film called Space: What’s in It for Me? was shown at the Air and Space Museum for a year.[17] Recently, NASM posted select portions from that film. Movie poster for the 2019 Nichols documentary Woman in Motion. (credit: Stars North Film)Woman in motionIn 2019, a documentary called Woman in Motion came out about the life of Nichelle Nichols. Produced and directed by Todd Thompson, the film succeeds in portraying the extensive career of an actress that most of us know for her pioneering role as Lieutenant Uhura in Star Trek. The film also uses material obtained from the NASA Headquarters History Office, specifically the executive report titled “Women in Motion” that summarizes the work Nichols’ did while under contract with NASA in 1977.In spite of a stroke she suffered in 2015, Nichols manages to remain a vivid on-screen presence in Thompson’s film. Viewers see an intelligent and talented individual who, even though touched by the debilitating effects of dementia, still impresses the viewer.The bulk of the production is comprised of film clips and interviews that tell the story of her life. Footage is used from an earlier documentary called Black Stars in Orbit that was directed by William Miles. His hour-long program was first broadcast on PBS in February 1990 and touches upon the racist policies that initially prevented Black pilots from participating in the space program as well as celebrating the accomplishments of those who finally did become astronauts. The full-length 52-minute interview that Miles conducted with Nichols for Black Stars in Orbit is available online through Washington University in St. Louis. Movie poster for the 2019 Nichols documentary Woman in Motion. (credit: Stars North Film)Woman in motionIn 2019, a documentary called Woman in Motion came out about the life of Nichelle Nichols. Produced and directed by Todd Thompson, the film succeeds in portraying the extensive career of an actress that most of us know for her pioneering role as Lieutenant Uhura in Star Trek. The film also uses material obtained from the NASA Headquarters History Office, specifically the executive report titled “Women in Motion” that summarizes the work Nichols’ did while under contract with NASA in 1977.In spite of a stroke she suffered in 2015, Nichols manages to remain a vivid on-screen presence in Thompson’s film. Viewers see an intelligent and talented individual who, even though touched by the debilitating effects of dementia, still impresses the viewer.The bulk of the production is comprised of film clips and interviews that tell the story of her life. Footage is used from an earlier documentary called Black Stars in Orbit that was directed by William Miles. His hour-long program was first broadcast on PBS in February 1990 and touches upon the racist policies that initially prevented Black pilots from participating in the space program as well as celebrating the accomplishments of those who finally did become astronauts. The full-length 52-minute interview that Miles conducted with Nichols for Black Stars in Orbit is available online through Washington University in St. Louis. Nichelle Nichols interview from Black Stars in Orbit, the 1990 documentary directed by William Miles. (credit: Washington University in St. Louis)In spite of a stroke she suffered in 2015, Nichols manages to remain a vivid on-screen presence in Thompson’s film. Viewers see an intelligent and talented individual who, even though touched by the debilitating effects of dementia, still impresses the viewer. Nichols’ words are carefully chosen and viewers can sense her frustration with the changes she has undergone. The audience gets used to the tempered rhythm of her speech and are rewarded by the prevailing power of her voice complimented by the intense fire that is still present in her eyes.Thompson’s film chronicles the amazing and diverse talents that Nichols had as a musical theater actor. Growing up in Chicago, one of six children, Nichols first performed in nightclubs and live stage productions including Broadway where she exhibited a skill as an accomplished singer and dancer. When she moved to Los Angeles, she began to act in television. She first met Gene Roddenberry when she appeared in a controversial episode of his short-lived TV series The Lieutenant (1963–1964).Colin O’Malley provides the documentary film with a score that is powerful but sometimes too melodramatic for the numerous snippets taken from her book-on-tape, archival interviews, graphics and testimonials. The quality and number of diverse interviews that Thompson was able to obtain are notable, including those with Astronomer Neil deGrasse Tyson and Nichols’ Star Trek series co-stars George Takei and Walter Koenig. Leading civil rights figures, including Dr. King’s son Rev. Martin Luther King III as well as Rev. Al Sharpton and Congresswoman Maxine Waters, are also featured. NASA astronauts Fred Gregory, Guy Bluford, and Bill Nelson (now the NASA administrator) are interviewed along with astronaut and former NASA administrator Charlie Bolden.Although it is just over 90 minutes in length, Thompson’s film could have been shorter. The first hour clips along pretty well but then the film features several dramatic false endings where the viewer thinks the film is winding down only to discover that it is not.In addition, there are factual errors. For example, near the end of the film, viewers see posted on the screen “NASA was so impressed with her results, they increased the 1978 astronaut class roster from 25 to 35.” Although NASA may have been impressed by Nichols’ work, the space agency did not raise but rather lowered the final number of astronauts selected. Space historian and author Michael Cassutt, in the biography The Astronaut Maker about George Abbey, the director of flight crew operations at the NASA Johnson Space Center and in charge of astronaut selection during Nichols’ contract, points out during that time, “forty new astronauts would be selected, twenty pilot and twenty mission specialists.” [18] However, there were still astronauts left over from the Apollo/Skylab programs and most of those were pilots. As a result, NASA reduced that number by 5 resulting in the final 35 selected for the 1978 Group 8 Astronaut Candidate class or “ASCANs.”Viewers watching the film through to the end will be treated to Nichols shown in a recording studio singing “Fly Me to the Moon” while the end credits roll by. The power of her voice during this session is incredible. According to director Thompson, “Nichelle previously recorded ‘Fly Me to the Moon’ on her birthday a few years back so that track was our original source. But then she sang it live for us in the studio as well during filming.”[19] Nichelle Nichols interview from Black Stars in Orbit, the 1990 documentary directed by William Miles. (credit: Washington University in St. Louis)In spite of a stroke she suffered in 2015, Nichols manages to remain a vivid on-screen presence in Thompson’s film. Viewers see an intelligent and talented individual who, even though touched by the debilitating effects of dementia, still impresses the viewer. Nichols’ words are carefully chosen and viewers can sense her frustration with the changes she has undergone. The audience gets used to the tempered rhythm of her speech and are rewarded by the prevailing power of her voice complimented by the intense fire that is still present in her eyes.Thompson’s film chronicles the amazing and diverse talents that Nichols had as a musical theater actor. Growing up in Chicago, one of six children, Nichols first performed in nightclubs and live stage productions including Broadway where she exhibited a skill as an accomplished singer and dancer. When she moved to Los Angeles, she began to act in television. She first met Gene Roddenberry when she appeared in a controversial episode of his short-lived TV series The Lieutenant (1963–1964).Colin O’Malley provides the documentary film with a score that is powerful but sometimes too melodramatic for the numerous snippets taken from her book-on-tape, archival interviews, graphics and testimonials. The quality and number of diverse interviews that Thompson was able to obtain are notable, including those with Astronomer Neil deGrasse Tyson and Nichols’ Star Trek series co-stars George Takei and Walter Koenig. Leading civil rights figures, including Dr. King’s son Rev. Martin Luther King III as well as Rev. Al Sharpton and Congresswoman Maxine Waters, are also featured. NASA astronauts Fred Gregory, Guy Bluford, and Bill Nelson (now the NASA administrator) are interviewed along with astronaut and former NASA administrator Charlie Bolden.Although it is just over 90 minutes in length, Thompson’s film could have been shorter. The first hour clips along pretty well but then the film features several dramatic false endings where the viewer thinks the film is winding down only to discover that it is not.In addition, there are factual errors. For example, near the end of the film, viewers see posted on the screen “NASA was so impressed with her results, they increased the 1978 astronaut class roster from 25 to 35.” Although NASA may have been impressed by Nichols’ work, the space agency did not raise but rather lowered the final number of astronauts selected. Space historian and author Michael Cassutt, in the biography The Astronaut Maker about George Abbey, the director of flight crew operations at the NASA Johnson Space Center and in charge of astronaut selection during Nichols’ contract, points out during that time, “forty new astronauts would be selected, twenty pilot and twenty mission specialists.” [18] However, there were still astronauts left over from the Apollo/Skylab programs and most of those were pilots. As a result, NASA reduced that number by 5 resulting in the final 35 selected for the 1978 Group 8 Astronaut Candidate class or “ASCANs.”Viewers watching the film through to the end will be treated to Nichols shown in a recording studio singing “Fly Me to the Moon” while the end credits roll by. The power of her voice during this session is incredible. According to director Thompson, “Nichelle previously recorded ‘Fly Me to the Moon’ on her birthday a few years back so that track was our original source. But then she sang it live for us in the studio as well during filming.”[19] NASA Public Service Award presented to Nichols on October 7, 1984 by astronaut Judy Resnik. (credit: Todd Thompson and Woman in Motion)“Hailing frequencies closed”Star Trek was an exception among the all-white television shows that dominated the networks of the 1960s. In spite of the fact that the show featured principal cast members of unconventional racial backgrounds, Roddenberry didn’t know what to do with women. For a supposedly very progressive show, it still had some very conservative leanings. There were still no women starship captains.The Civil Rights Act of 1964, followed by the Equal Employment Opportunities Act of 1972, showed that the workplace in America was being transformed by the social activism of the time. More rights for African Americans were among the results and, by the time of the airing of the first episode of Star Trek on September 8, 1966, NASA already had in place policies against discrimination that included not only race and gender, but also physical handicaps. NASA Public Service Award presented to Nichols on October 7, 1984 by astronaut Judy Resnik. (credit: Todd Thompson and Woman in Motion)“Hailing frequencies closed”Star Trek was an exception among the all-white television shows that dominated the networks of the 1960s. In spite of the fact that the show featured principal cast members of unconventional racial backgrounds, Roddenberry didn’t know what to do with women. For a supposedly very progressive show, it still had some very conservative leanings. There were still no women starship captains.The Civil Rights Act of 1964, followed by the Equal Employment Opportunities Act of 1972, showed that the workplace in America was being transformed by the social activism of the time. More rights for African Americans were among the results and, by the time of the airing of the first episode of Star Trek on September 8, 1966, NASA already had in place policies against discrimination that included not only race and gender, but also physical handicaps. Photo showing Nichols with NASA engineer Dr. Jesco von Puttkamer and shuttle astronaut Judith Resnik. (credit: Todd Thompson and Woman in Motion)Margaret A. Weitekamp, curator of Social and Cultural Dimensions of the Spaceflight Collection at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, writes, “The astronaut corps recruited by the NASA in the late 1970s owed at least part of its racial and gender diversity to Nichols and her fame as Lt. Uhura. The evolution of the Uhura character both reflected—and spurred—historical changes for women and people of color in postwar America.”[20]While Nichols acknowledges that “the precise reasons for the significant increase [in NASA astronaut office applications] cannot be wholly attributed to the specific efforts of this contract,” one cannot rule out her work over a relatively short period of time motivating others to at least take notice of what NASA was doing and to perhaps consider working for them.Nichols’ contract with NASA resulted in altering perceptions within the space agency not only changing how NASA hired people, but also how it chose them for its astronaut corps. Mae Jemison, the first African-American woman astronaut and Judith Resnik, NASA’s first Jewish-American astronaut, both attributed their space careers to Nichols’ recruitment efforts. Before her untimely death in the Challenger accident in 1986, Resnik presented Nichols with NASA’s Public Service Award. In a tribute to Nichols’ influence, Jemison appeared as a transporter operator in a 1993 episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Photo showing Nichols with NASA engineer Dr. Jesco von Puttkamer and shuttle astronaut Judith Resnik. (credit: Todd Thompson and Woman in Motion)Margaret A. Weitekamp, curator of Social and Cultural Dimensions of the Spaceflight Collection at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, writes, “The astronaut corps recruited by the NASA in the late 1970s owed at least part of its racial and gender diversity to Nichols and her fame as Lt. Uhura. The evolution of the Uhura character both reflected—and spurred—historical changes for women and people of color in postwar America.”[20]While Nichols acknowledges that “the precise reasons for the significant increase [in NASA astronaut office applications] cannot be wholly attributed to the specific efforts of this contract,” one cannot rule out her work over a relatively short period of time motivating others to at least take notice of what NASA was doing and to perhaps consider working for them.Nichols’ contract with NASA resulted in altering perceptions within the space agency not only changing how NASA hired people, but also how it chose them for its astronaut corps. Mae Jemison, the first African-American woman astronaut and Judith Resnik, NASA’s first Jewish-American astronaut, both attributed their space careers to Nichols’ recruitment efforts. Before her untimely death in the Challenger accident in 1986, Resnik presented Nichols with NASA’s Public Service Award. In a tribute to Nichols’ influence, Jemison appeared as a transporter operator in a 1993 episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation. One of the many fan letters that Nichols received during her career. (credit: Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Headquarters History Office)While Nichols acknowledges that “the precise reasons for the significant increase [in NASA astronaut office applications] cannot be wholly attributed to the specific efforts of this contract,”[21] one cannot rule out her work over a relatively short period of time motivating others to at least take notice of what NASA was doing and to perhaps consider working for them. In the executive summary of her contract report she wrote that “perhaps our efforts, or push towards a racially, culturally and mixed space program are not ours at all, but merely the pull of the ethically balanced Star Trek Universe that lies in our future.”On the final page of that her report, Nichols wrote:WOMEN IN MOTION, INC. TO NASA HEADQUARTERS… THE MELODY LINGERS ON… WE STILL GET LETTERS… TELEPHONE CALLS… INTERNATIONAL NEWS AND PRESS COVERAGE… REQUESTS TO APPEAR, TO SPEAK ON NASA CONTRACT AT ORGANIZATIONS AND SCHOOLS, CHURCHES OTHER RELATED INQUIRIES… THE NASA BEAT GOES ON…PPS ENTIRE CREW RESPECTFULLY REQUESTS SHORE LEAVE…Thanks to Nichols work, Americans have come to expect greater diversity from NASA even though it took until 2022, the year that Nichelle Nichols died, for the first Black woman astronaut, Jessica Watkins, to be part of a crew aboard the International Space Station. It is hoped that in the coming years ahead, even greater efforts by the space agency will bring equity, like that envisioned by Star Trek, that much closer to reality. One of the many fan letters that Nichols received during her career. (credit: Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Headquarters History Office)While Nichols acknowledges that “the precise reasons for the significant increase [in NASA astronaut office applications] cannot be wholly attributed to the specific efforts of this contract,”[21] one cannot rule out her work over a relatively short period of time motivating others to at least take notice of what NASA was doing and to perhaps consider working for them. In the executive summary of her contract report she wrote that “perhaps our efforts, or push towards a racially, culturally and mixed space program are not ours at all, but merely the pull of the ethically balanced Star Trek Universe that lies in our future.”On the final page of that her report, Nichols wrote:WOMEN IN MOTION, INC. TO NASA HEADQUARTERS… THE MELODY LINGERS ON… WE STILL GET LETTERS… TELEPHONE CALLS… INTERNATIONAL NEWS AND PRESS COVERAGE… REQUESTS TO APPEAR, TO SPEAK ON NASA CONTRACT AT ORGANIZATIONS AND SCHOOLS, CHURCHES OTHER RELATED INQUIRIES… THE NASA BEAT GOES ON…PPS ENTIRE CREW RESPECTFULLY REQUESTS SHORE LEAVE…Thanks to Nichols work, Americans have come to expect greater diversity from NASA even though it took until 2022, the year that Nichelle Nichols died, for the first Black woman astronaut, Jessica Watkins, to be part of a crew aboard the International Space Station. It is hoped that in the coming years ahead, even greater efforts by the space agency will bring equity, like that envisioned by Star Trek, that much closer to reality. Nichelle Nichols speaks in front of the Space Shuttle Endeavour in Los Angeles on September 21, 2012. (credit: Reed Saxon/Associated Press.)ReferencesWoman in Motion, directed by Todd Thompson (A Stars North Film, 2019)Allan Asherman, June 9, 1987 Interview by Allan Asherman, The Star Trek Interview Book, (New York: Pocket Books, 1988), p. 69.Ebony, January 1967, pp. 70-76.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), p. 209.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), p. 222.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), p. 219.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.“Symposium ’77 to draw 2,000 students,” NASA Roundup, Vol. 16, No. 4, February 18, 1977, p. 1.Woman in Motion, directed by Todd Thompson (A Stars North Film, 2019). Nichelle Nichols is speaking from an interview done on March 16, 1989 for the documentary Black Stars in Orbit.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Nichols interview by Margaret A. Weitekamp, May 24, 2022, “More Than “Just Uhura:” Understanding Star Trek’s Lt. Uhura, Civil Rights, and Space History”, p. 17 Star Trek and History, Wiley Pop Culture and History Series, edited by Nancy Reagin, pp. 22-38. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), p. 225.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), pp. 229-230.Michael Cassutt, The Astronaut Maker: How One Mysterious Engineer Ran Human Spaceflight for a Generation, (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2018), p. 175.Todd Thompson, email exchange with author, January 8, 2022.Weitekamp, Margaret A., “More Than Just Uhura”: Understanding Star Trek’s Lt. Uhura, Civil Rights, and History.” In Star Trek and History, edited by Nancy R. Reagin, pp. 22-38. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Glen E. Swanson is the former historian of the NASA Johnson Space Center and founder of Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly. Glen is currently working on a book on how scientifically knowledgeable agencies and organizations like NASA and the aerospace industry guided the creation of popular fiction and influenced the Hollywood of the 1960s with a special emphasis on the original Star Trek television series. If anyone knows of a good publisher or agent, he can be reached at glenswanson@cspace.siteNote: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account. Nichelle Nichols speaks in front of the Space Shuttle Endeavour in Los Angeles on September 21, 2012. (credit: Reed Saxon/Associated Press.)ReferencesWoman in Motion, directed by Todd Thompson (A Stars North Film, 2019)Allan Asherman, June 9, 1987 Interview by Allan Asherman, The Star Trek Interview Book, (New York: Pocket Books, 1988), p. 69.Ebony, January 1967, pp. 70-76.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), p. 209.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), p. 222.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), p. 219.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.“Symposium ’77 to draw 2,000 students,” NASA Roundup, Vol. 16, No. 4, February 18, 1977, p. 1.Woman in Motion, directed by Todd Thompson (A Stars North Film, 2019). Nichelle Nichols is speaking from an interview done on March 16, 1989 for the documentary Black Stars in Orbit.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Nichols interview by Margaret A. Weitekamp, May 24, 2022, “More Than “Just Uhura:” Understanding Star Trek’s Lt. Uhura, Civil Rights, and Space History”, p. 17 Star Trek and History, Wiley Pop Culture and History Series, edited by Nancy Reagin, pp. 22-38. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), p. 225.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, (New York: G.P. Putham’s Sons, 1994), pp. 229-230.Michael Cassutt, The Astronaut Maker: How One Mysterious Engineer Ran Human Spaceflight for a Generation, (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2018), p. 175.Todd Thompson, email exchange with author, January 8, 2022.Weitekamp, Margaret A., “More Than Just Uhura”: Understanding Star Trek’s Lt. Uhura, Civil Rights, and History.” In Star Trek and History, edited by Nancy R. Reagin, pp. 22-38. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.Women in Motion, Incorporated, NASA Contract NASW-3049, “Final Report by Women in Motion, Inc.,” August 10, 1977, NASA Astronaut Recruitment (Nichelle Nichols) Report file, 8935, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, DC.Glen E. Swanson is the former historian of the NASA Johnson Space Center and founder of Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly. Glen is currently working on a book on how scientifically knowledgeable agencies and organizations like NASA and the aerospace industry guided the creation of popular fiction and influenced the Hollywood of the 1960s with a special emphasis on the original Star Trek television series. If anyone knows of a good publisher or agent, he can be reached at glenswanson@cspace.siteNote: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account. |

The Zeiss refracting telescope at Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles.Gabriella Angotti-Jones for The New York Times

The Zeiss refracting telescope at Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles.Gabriella Angotti-Jones for The New York Times Tourists and locals enjoying the sunset at the Griffith Observatory, home to the Zeiss telescope.Gabriella Angotti-Jones for The New York Times

Tourists and locals enjoying the sunset at the Griffith Observatory, home to the Zeiss telescope.Gabriella Angotti-Jones for The New York Times The Zeiss telescope after viewing hours last month.Gabriella Angotti-Jones for The New York Times

The Zeiss telescope after viewing hours last month.Gabriella Angotti-Jones for The New York Times Griffith Observatory

Griffith Observatory High-resolution imaging satellites, like the Skysat series operated by Planet, have had a major effect on the war in Ukraine. (credit: Maxar)

High-resolution imaging satellites, like the Skysat series operated by Planet, have had a major effect on the war in Ukraine. (credit: Maxar)

NASA’s Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft on the pad for the Artemis 1 launch, scheduled for the morning of August 29. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky)The time has finally come for Artemis 1by Jeff Foust

NASA’s Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft on the pad for the Artemis 1 launch, scheduled for the morning of August 29. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky)The time has finally come for Artemis 1by Jeff Foust An overview of the Artemis 1 mission (

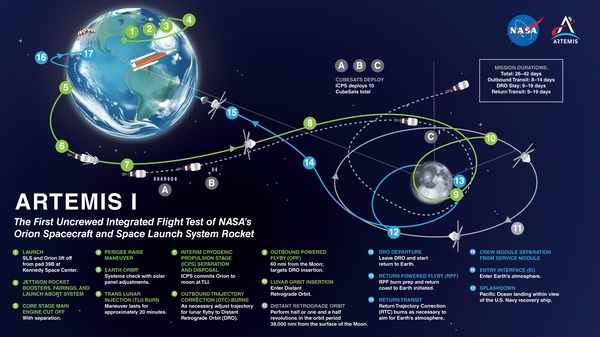

An overview of the Artemis 1 mission ( SLS arrive at the pad last week for the Artemis 1 launch. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky)Other mission objectivesArtemis 1 has a fourth mission objective beyond reentry, testing of SLS and Orion systems, and recovering Orion after splashdown. The “additional flight test objectives” is a catch-all for a range of other tests on Orion during the mission, testing various spacecraft technologies from radiators to cameras mounted on the tips of its solar arrays.There are also payloads inside Orion that will be tested during the flight. Mannequins will measure the radiation environment that astronauts will be exposed to during a flight as well as the effectiveness of a vest to shield astronauts from that radiation. Lockheed Martin, working with Cisco WebEx and Amazon, will test the use of Amazon’s Alexa voice-based computing system inside Orion.Rob Chambers, director of commercial civil space strategy at Lockheed Martin, said in a briefing last week he expected to get a puzzled response from Amazon when contacting them about participating in the project, called Callisto. “Instead, they explained that one of the progenitors for Alexa, one of the thoughts that they had, if you will, was the voice computer from the Starship Enterprise,” he recalled. “In some ways, they said, they had been kind of waiting for this moment.”Artemis 1 will, in addition to Orion and its payloads inside, fly ten cubesat secondary payloads. The ten 6U cubesats, from NASA, international partners, and other organizations, will carry out a variety of missions, from orbiting and even landing on the Moon to testing deep-space communications technologies and using a solar sail to fly by an asteroid.That is, if the cubesats work. NASA required the cubesats to be delivered nearly a year ago so they could be installed on a payload adapter, on top of which Orion was attached. Once Orion was installed, those cubesats were inaccessible. While five of the cubesats had the ability to recharge their batteries, the other five, for various reasons, did not, raising concerns that by the time they launch, their batteries will be dead. Those cubesats have solar panels, but a lack of battery power could disrupt critical early operations after deployment from the SLS.“We’re trying to work through the preparations and get the SLS ready to fly. That’s the best thing we can do at this point,” said Jacob Bleacher, NASA chief exploration scientist, when asked about the battery issues with the cubesats at a briefing last week. “If we can get the SLS off at the end of this month or early September, we hope that they’ll all have an opportunity to be able to fly.”Craig Hardgrove, principal investigator for one of the cubesats, LunaH-Map, said the inability to charge that cubesat came out of prelaunch reviews. “The SLS program didn’t feel comfortable with us charging,” he said, but didn’t elaborate. Even if battery levels drop below the minimum needed to start its flight computer after deployment, he said two exposed solar arrays should generate enough power to charge the batteries “in not too much time.”Another cubesat identified by NASA as not being able to charge is Team Miles, which won its spot on the mission through the Centennial Challenges prize program. Wesley Faler, leader of Team Miles, said that was a deliberate choice. “We had an opportunity to charge but we opted out of it,” he said, based on the low rate of battery discharge. “We figured, why rock the boat and introduce the variable of recharging?”Planning for the futureAs NASA moves into the final stages of preparations for Artemis 1, it is also moving ahead on Artemis 2, the first crewed flight. That mission is likely to launch no earlier than late 2024, depending in part on the outcome of Artemis 1.“As long as you are healthy,” Wiseman said, “we’re going to load you on a rocket and shoot you off the planet.”NASA has yet to announce who will fly on the mission, although one of the four seats will go to a Canadian astronaut as part of an agreement between NASA and the Canadian Space Agency whereby Canada provides a robotic arm for the lunar Gateway. Canada, in return, gets a seat on Artemis 2 and a later Gateway mission.“The question everyone will ask is when are we assigning a crew to Artemis 2? We hope that will be later this year,” said Reid Wiseman, NASA chief astronaut, at a briefing earlier this month.In late 2020, NASA announced the selection of 18 astronauts as part of an “Artemis Team” that would be considered for future Artemis flight assignments. That announcement came at a National Space Council meeting where outgoing Vice President Mike Pence announced the 18 astronauts, calling them “heroes of the future.”However, Wiseman said that the entire astronaut corps of 42 active astronauts (with ten more in training) would be considered for Artemis 2 and later missions, not just the Artemis Team astronauts, a point he emphasized several times at that briefing.“The way I look at it, any one of our 42 active astronauts is eligible for an Artemis mission,” he said, a point he emphasized several times during the briefing. “We want to assemble the right team for this mission.”NASA, he also said, was changing radiation standards based on recommendations from a National Academies study last year, doing away with separate standards based on age and gender to a single one. Doing so, that study argued, would provide more flight opportunities for women who previously had a lower radiation standard.“As long as you are healthy,” he said, “we’re going to load you on a rocket and shoot you off the planet.” But first, Artemis 1 has to demonstrate that the rocket, and the spacecraft, are ready for astronauts.Jeff Foust (

SLS arrive at the pad last week for the Artemis 1 launch. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky)Other mission objectivesArtemis 1 has a fourth mission objective beyond reentry, testing of SLS and Orion systems, and recovering Orion after splashdown. The “additional flight test objectives” is a catch-all for a range of other tests on Orion during the mission, testing various spacecraft technologies from radiators to cameras mounted on the tips of its solar arrays.There are also payloads inside Orion that will be tested during the flight. Mannequins will measure the radiation environment that astronauts will be exposed to during a flight as well as the effectiveness of a vest to shield astronauts from that radiation. Lockheed Martin, working with Cisco WebEx and Amazon, will test the use of Amazon’s Alexa voice-based computing system inside Orion.Rob Chambers, director of commercial civil space strategy at Lockheed Martin, said in a briefing last week he expected to get a puzzled response from Amazon when contacting them about participating in the project, called Callisto. “Instead, they explained that one of the progenitors for Alexa, one of the thoughts that they had, if you will, was the voice computer from the Starship Enterprise,” he recalled. “In some ways, they said, they had been kind of waiting for this moment.”Artemis 1 will, in addition to Orion and its payloads inside, fly ten cubesat secondary payloads. The ten 6U cubesats, from NASA, international partners, and other organizations, will carry out a variety of missions, from orbiting and even landing on the Moon to testing deep-space communications technologies and using a solar sail to fly by an asteroid.That is, if the cubesats work. NASA required the cubesats to be delivered nearly a year ago so they could be installed on a payload adapter, on top of which Orion was attached. Once Orion was installed, those cubesats were inaccessible. While five of the cubesats had the ability to recharge their batteries, the other five, for various reasons, did not, raising concerns that by the time they launch, their batteries will be dead. Those cubesats have solar panels, but a lack of battery power could disrupt critical early operations after deployment from the SLS.“We’re trying to work through the preparations and get the SLS ready to fly. That’s the best thing we can do at this point,” said Jacob Bleacher, NASA chief exploration scientist, when asked about the battery issues with the cubesats at a briefing last week. “If we can get the SLS off at the end of this month or early September, we hope that they’ll all have an opportunity to be able to fly.”Craig Hardgrove, principal investigator for one of the cubesats, LunaH-Map, said the inability to charge that cubesat came out of prelaunch reviews. “The SLS program didn’t feel comfortable with us charging,” he said, but didn’t elaborate. Even if battery levels drop below the minimum needed to start its flight computer after deployment, he said two exposed solar arrays should generate enough power to charge the batteries “in not too much time.”Another cubesat identified by NASA as not being able to charge is Team Miles, which won its spot on the mission through the Centennial Challenges prize program. Wesley Faler, leader of Team Miles, said that was a deliberate choice. “We had an opportunity to charge but we opted out of it,” he said, based on the low rate of battery discharge. “We figured, why rock the boat and introduce the variable of recharging?”Planning for the futureAs NASA moves into the final stages of preparations for Artemis 1, it is also moving ahead on Artemis 2, the first crewed flight. That mission is likely to launch no earlier than late 2024, depending in part on the outcome of Artemis 1.“As long as you are healthy,” Wiseman said, “we’re going to load you on a rocket and shoot you off the planet.”NASA has yet to announce who will fly on the mission, although one of the four seats will go to a Canadian astronaut as part of an agreement between NASA and the Canadian Space Agency whereby Canada provides a robotic arm for the lunar Gateway. Canada, in return, gets a seat on Artemis 2 and a later Gateway mission.“The question everyone will ask is when are we assigning a crew to Artemis 2? We hope that will be later this year,” said Reid Wiseman, NASA chief astronaut, at a briefing earlier this month.In late 2020, NASA announced the selection of 18 astronauts as part of an “Artemis Team” that would be considered for future Artemis flight assignments. That announcement came at a National Space Council meeting where outgoing Vice President Mike Pence announced the 18 astronauts, calling them “heroes of the future.”However, Wiseman said that the entire astronaut corps of 42 active astronauts (with ten more in training) would be considered for Artemis 2 and later missions, not just the Artemis Team astronauts, a point he emphasized several times at that briefing.“The way I look at it, any one of our 42 active astronauts is eligible for an Artemis mission,” he said, a point he emphasized several times during the briefing. “We want to assemble the right team for this mission.”NASA, he also said, was changing radiation standards based on recommendations from a National Academies study last year, doing away with separate standards based on age and gender to a single one. Doing so, that study argued, would provide more flight opportunities for women who previously had a lower radiation standard.“As long as you are healthy,” he said, “we’re going to load you on a rocket and shoot you off the planet.” But first, Artemis 1 has to demonstrate that the rocket, and the spacecraft, are ready for astronauts.Jeff Foust (

Nichelle Nichols is shown in NASA’s Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center in March 1977. (credit: NASA)Chief communicator: How Star Trek’s Lieutenant Uhura helped NASAby Glen E. Swanson