Month: July 2023

Space X Starship Could Alleviate Climate Change

A Brilliant Idea For Trips To Mars!!

The End Of An Era In European Spaceflight

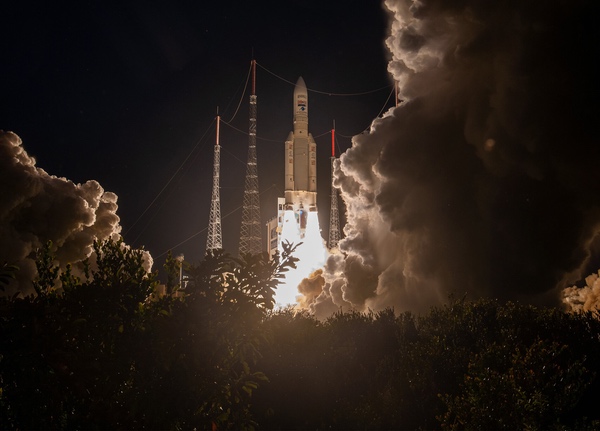

An Ariane 5 lifts off for the 117th and final time July 5 from French Guiana. (credit: ESA-CNES-Arianespace/Optique video du CSG/P. Piron) An Ariane 5 lifts off for the 117th and final time July 5 from French Guiana. (credit: ESA-CNES-Arianespace/Optique video du CSG/P. Piron) |

A crisis and an opportunity for European space access

by Jeff Foust

Monday, July 10, 2023

Two launches this month illustrated the current state of European access to space.

Last Wednesday, an Ariane 5 lifted off from Kourou, French Guiana. It was, in many respects, a typical Ariane 5 launch, carrying two communications satellites bound for geostationary orbit. One, Heinrich-Hertz-Satellit, was built by German company OHB for the German government to test advanced communications technologies. The other, Syracuse 4B, was built by a consortium of Airbus Defence and Space and Thales Alenia Space to provide communications for the French military.

| “Ariane 5 is now over, and Ariane 5 has perfectly finished its work and really is now a legendary launcher,” said Israël. “But Ariane 6 is coming.” |

It was the 117th Ariane 5 launch over 27 years. It was also the last Ariane 5 launch, a retirement set in motion years ago. After a shaky start—its inaugural launch in June 1996 “did not result in validation of Europe’s new launcher,” in the infamous phrase of a European Space Agency press release about its explosive failure—it became one of the most reliable launch vehicles available. In its last 20 years of operations, the only black mark on its record was a 2018 launch where an incorrect value in an inertial reference system caused it to place its payloads into an incorrect, but recoverable, orbit.

For much of its career, Ariane 5 was a major player—arguably the major vehicle—in the commercial launch market in an era dominated by GEO communications satellites. It launched several key science missions for the European Space Agency as well as cargo spacecraft for the International Space Station. Perhaps its highest profile mission was the Christmas morning 2021 launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, placing the $10 billion spacecraft on a trajectory so accurate it effectively doubled the spacecraft’s lifetime by allowing propellant set aside for trajectory correction maneuvers to instead be used for later stationkeeping at the Earth-Sun L-2 point.

“Ariane 5 is now over, and Ariane 5 has perfectly finished its work and really is now a legendary launcher,” said Arianespace CEO Stéphane Israël after the deployment of the two satellites on last week’s launch. “But Ariane 6 is coming.”

But the problem for Arianespace, ESA, and Europe’s space industry in general is that Ariane 6 is not yet here. Original plans called for the end of the Ariane 5 to overlap with the start of the Ariane 6, in much the same way as the Ariane 5 overlapped with Ariane 4, which made its final launch in 2003. That would allow for a smooth transition from one vehicle to the next.

However, Ariane 6, once slated to make its debut in 2020, is years behind schedule. That is not necessarily a surprise, given that other new launch vehicles are also well behind schedule. ULA’s Vulcan Centaur’s first launch, also once targeted for 2020, is now delayed until later this year when the company concluded it needed to reinforce part of the Centaur upper stage after a test mishap this spring. Blue Origin’s New Glenn is not expected to fly until at least next year after extended delays. Japan’s H3 rocket, also delayed by years, launched in March, only to fail shortly after stage separation.

ESA announced last October it expected Ariane 6 to make its first launch in the fourth quarter of this year. Both ESA and Arianespace, though, have declined to provide updates, saying they will wait until after more ground tests are completed this summer.

“We have to go through a number of technical milestones over the summer period but I promise, after the summer in September, we will indicate a period which is the target period for the Ariane 6,” said ESA director general Josef Aschbacher during a briefing June 29 after a meeting of the ESA Council in Stockholm.

It is increasingly unlikely, though, that Ariane 6 will be able to make its debut this year. In May, executives with OHB, which produces components for the Ariane 6, said in an earnings call that they expected the first Ariane 6 launch to take place in early 2024, the first formal indication that the launch would slip beyond this year.

“I am getting more and more confident we will see the first launch of Ariane 6 early next year,” said OHB CEO Marco Fuchs. “I think we are within a year of the first launch and that is psychologically very important.”

While ESA has declined to set a new launch date for the Ariane 6, it has provided updates on its development. The most recent one, published June 8, set out a schedule for upcoming tests and reviews for the vehicle. In November, it stated, assembly of the first flight version of the Ariane 6 would begin in Kourou, including a wet dress rehearsal. That schedule would give little time for an Ariane 6 launch before the end of the year even if everything went perfectly—and, so far, things have not gone perfectly.

The first Vega C launch in July 2022. The rocket remains grounded after a failure on its second launch last December. (credit: ESA/M. Pedoussaut) The first Vega C launch in July 2022. The rocket remains grounded after a failure on its second launch last December. (credit: ESA/M. Pedoussaut) |

Launcher crisis

The delays in Ariane 6 would be an embarrassment, but little else, if that was the only problem for Europe’s launch industry. Instead, it is one of several problems that has temporarily grounded the continent.

Until last year, Europe had relied on three vehicles to launch nearly any spacecraft. For large satellites, there was the Ariane 5 and, soon, Ariane 6. Smaller satellites were served by the Vega and an impending upgrade, Vega C. In between the two was the Russian Soyuz, launching commercial and European government spacecraft from French Guiana.

| ““If, for a couple of months, there’s not a rocket available, it’s bad enough. I’m the first one to call this a crisis,” said Aschbacher. “But this is not something permanent.” |

However, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and sanctions by Europe in response, Russia halted Soyuz launch operations in French Guiana, stranding payloads such as ESA science missions and Galileo navigation satellites. In December, the second Vega C suffered a failure in the Zefiro 40 motor that powers its second stage, destroying two commercial high-resolution imaging satellites.

An investigation traced the failure to a flawed carbon-carbon insert in the nozzle of the motor. Avio, the Italian prime contractor for Vega C, said it would replace that component with one from a new supplier and conduct tests that would allow the vehicle to return to flight before the end of the year. (The original Vega vehicle, which does not use the Zefiro 40 motor, will resume launches in September, but most of the missions on the Vega manifest are for the more powerful Vega C.)

Those return-to-flight activities included a static-fire test of the Zefiro 40 motor. However, Avio announced June 29 that the test, which took place the day before, suffered an anomaly of some kind where the motor’s chamber pressure dropped 40 seconds into the 97-second test.

Avio said it did not know what caused the pressure drop but said that the new carbon-carbon component did not appear to be at fault. “This aspect will require further investigation and testing activity to be conducted by Avio and the European Space Agency to ensure optimal performance conditions,” the company said in a statement about the test.

That setback makes it unlikely the Vega C will return to flight this year. “We have to see in detail what this anomaly will mean” for those plans, ESA’s Aschbacher said at the ESA Council briefing. “This will have an impact because it was a very important milestone on our roadmap to the return to flight for Vega C.”

The problems with Vega C, continued delays with Ariane 6, and the loss of the Soyuz for geopolitical reasons mean that, with last week’s Ariane 5 retirement, Europe temporarily lacks the means to launch its own satellites. That is something that Aschbacher has often called a “crisis” while emphasizing its temporary nature.

“If, for a couple of months, there’s not a rocket available, it’s bad enough. I’m the first one to call this a crisis,” he said at the “Investing in Space” conference by the Financial Times last month. “But this is not something permanent.”

The Falcon 9 carrying ESA’s Euclid on the launch pad several hours before its July 1 launch. (credit: J. Foust) The Falcon 9 carrying ESA’s Euclid on the launch pad several hours before its July 1 launch. (credit: J. Foust) |

Falcon to the rescue

The other launch that illustrated the current state of European space access took place four days and 4,000 kilometers from the final Ariane 5 flight. A Falcon 9 lifted off from Cape Canaveral July 1, much like dozens of other launches that SpaceX rocket has conducted so far this year. The big difference was its payload: a $1.5-billion space telescope—or, more precisely, a €1.4-billion European space telescope.

| “We were left completely in nowhere land, without any launcher,” said Racca. “It was an incredibly tense period because, in front of us, was the prospect of having to store the spacecraft for two years or more.” |

The Euclid spacecraft is a mission to study two of the biggest mysteries in cosmology: dark energy and dark matter, which combined comprise 95% of the universe. Equipped with a camera operating at visible wavelengths and a near-infrared spectrometer and photometer, astronomers will use Euclid to map a third of the sky, creating the most detailed 3-D map yet of the universe that can help them shed light on the nature of dark energy and dark matter.

“Euclid should provide a decisive response on the nature of dark energy,” said Yannick Mellier, an astronomer at the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris and leader of the Euclid Consortium, during a pre-launch press conference last month.

ESA had planned to launch Euclid to the Earth-Sun L-2 point on a Soyuz rocket, but when that rocket became unavailable last year, the agency had few options, particularly given the delays on the Ariane 6.

“We were left completely in nowhere land, without any launcher,” said Giuseppe Racca, Euclid project manager at ESA. “It was an incredibly tense period because, in front of us, was the prospect of having to store the spacecraft for two years or more.”

Last October, ESA announced it would instead launch Euclid on a Falcon 9. Euclid is not the first ESA mission to launch on a Falcon 9. Sentinel-6A, an Earth science spacecraft also known as Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich and developed in cooperation with NASA and other agencies in both the US and Europe, launched on a Falcon 9 in 2020. That launch, though, was provided by NASA as part of its contribution to the mission. In this case, ESA worked directly with SpaceX to arrange the launch of Euclid. (NASA is a partner on Euclid, providing infrared detectors for an instrument and hosting a data center, but was not involved in arranging the Falcon 9 launch.)

ESA officials said discussions with SpaceX started in May of last year, when a company executive told them they would have room on its manifest for Euclid in July of 2023. A three-month feasibility study followed to see if any changes were needed to the spacecraft because of the different launch environment of the Falcon 9, followed by tests to verify that assessment. “We can launch in July because did not have to change any of the hardware,” said Paolo Musi, Euclid program manager at Thales Alenia Space, the prime contractor for Euclid.

While ESA announced last October it would launch Euclid on a Falcon 9, the contract for that launch wasn’t finalized until late January. “We had to squash what we normally do in three years into five months,” said Mike Healy, head of science projects at ESA.

There was, he suggested, a bit of a culture clash between the Europeans and SpaceX. “There are too many differences to say,” he said. “They’re very can-do, can solve problems as we go along,” he said of SpaceX. “I think the European way is much more that we’ll optimize the process and make sure that we have to follow the process.”

“We had to adapt to each other. They were not used to us and we are not really used to them,” said Racca. “But I’m very happy with the relationship we had with SpaceX.”

There were technical challenges to overcome as well as regulatory ones. “The whole ITAR import-export control stuff is painful. That’s not SpaceX’s fault but that’s the reality,” Healy said. On past missions, like Sentinel-6, NASA handled that, but this time ESA and SpaceX had to grapple with those challenges. “But that’s just the environment that we face, and we managed to find solutions in a very short period of time to everything, so it can’t be that difficult.”

ESA officials declined to say how much they paid for the Falcon 9 launch, citing the commercial nature of the contract. Industry sources said that ESA paid a small premium over the list price of the Falcon 9, currently $67 million, to cover special mission requirements like enhanced cleanliness to avoid contamination of Euclid’s optics.

| “They’re very can-do, can solve problems as we go along,” Healy said of SpaceX. “I think the European way is much more that we’ll optimize the process and make sure that we have to follow the process.” |

Healy said ESA would do a more formal lessons-learned review after the launch, which will be useful since Euclid is not a one-off mission for the agency. When ESA announced last October it would launch Euclid on a Falcon 9, it also said it would move its Hera asteroid mission from an Ariane 6 to Falcon 9 to keep it on schedule for launch in October 2024. Hera will travel to the near Earth asteroid Didymos and its moon Dimorphos, which was the target for NASA’s DART mission last September.

At the ESA Council meeting last month, member states agreed to launch a third mission on Falcon 9. EarthCARE, an Earth science mission, was originally manifested on a Soyuz but moved last October to Vega C. Last December’s Vega C failure, along with changes in the design of the spacecraft itself, led ESA to switch the mission to a Falcon 9 launching in the second quarter of 2024.

Aschbacher said that the EarthCARE spacecraft’s dimensions had increased since the decision to move it to Vega C, which would have required modifications to the payload fairing of the rocket. The panel that investigated the Vega C failure recommended no changes in the configuration of the rocket through its initial launches. Given that assessment and the recent failure, ESA’s inspector general recommended not launching the mission on Vega C, he said.

Besides the ESA missions, there are also several Galileo spacecraft that need to launch next year that can no longer fly on Soyuz. At the ESA Council briefing, Javier Benedicto, ESA’s director of navigation, said discussions were underway with SpaceX for launching up to four Galileo satellites on Falcon 9 rockets, pending both technical analyses and the completion of a European Union security agreement.

The decision to launch Galileo satellites on Falcon 9 will be up to the EU, Aschbacher said, with ESA providing technical support. “We have provided all the technical information with regards to launcher compatibility, which the [European] Commission has,” he said after the Euclid launch. “Now it’s up to them to make a decision.”

While ESA’s near-term priority is getting Ariane 6 and Vega C flying, and relying on Falcon 9 in the interim, the agency sees the launcher crisis as an opportunity for longer-term changes in European space access. ESA is preparing for a European Space Summit in Seville, Spain, in November that will bring together both ESA and EU member states to discuss space priorities.

That will include proposals for a long-term space access strategy. “It’s really the larger picture of how Europe wants to establish itself in access to space,” Aschbacher said earlier this year. “It’s clear that the current situation needs a deeper reflection on the launcher sector in Europe.”

ESA hasn’t disclosed details of what might go into that strategy, but it will likely incorporate commercial developments in Europe as several companies work on small launch vehicles that have, so far, received only modest government support. Companies like Isar Aerospace and Rocket Factory Augsburg in Germany may be ready for their first launches before the end of the year, with other ventures also working on vehicles expects to fly in the next few years.

There is also the issue of looking beyond the Ariane 6 at what might follow. Europe developed Ariane 6 in part as a response to the rise of the Falcon 9, offering a vehicle that would be at least somewhat competitive in price. But Ariane 6 does not include any reusable elements—indeed, European officials often seemed skeptical about the benefits of reusability during the development of Ariane 6.

| “It’s clear that the current situation needs a deeper reflection on the launcher sector in Europe,” Aschbacher said earlier this year. |

But Falcon 9’s success in reusing boosters, enabling high flight rates and reduced costs, has prompted a reconsideration of the benefits of reusability. There have been some efforts to investigate reusability in Europe, including a methane-fueled reusable engine called Prometheus that underwent a static-fire test in June as part of a reusable stage demonstrator called Themis. But it’s unclear when, or how, that might translate into a vehicle with the kind of reuse that Falcon 9 demonstrates today, and other vehicles, like New Glenn, plan to offer in the next few years.

The near-term future of Ariane 6 is secure: once the vehicle does start flying, its manifest is full for a few years with European government missions as well as a large order from Amazon’s Project Kuiper constellation. What happens after that, though, is less clear.

“We are in a crisis and we should use the opportunity to convert this crisis into actions and changes that need to be adopted in order, in the future, to develop a robust launcher system for Europe,” Aschbacher said after the launch of Euclid, but was convinced the current crisis—a lack of any ability for Europe to launch payloads—will soon pass. “Then this few months will be a blip.”

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

The summer space-themed reality show “Stars on Mars” sends its participants on missions inspired by the 2015 movie The Martian. The show is more clever and watchable than you would expect. It airs Monday nights on Fox and streams on Hulu. (credit: Fox Television) The summer space-themed reality show “Stars on Mars” sends its participants on missions inspired by the 2015 movie The Martian. The show is more clever and watchable than you would expect. It airs Monday nights on Fox and streams on Hulu. (credit: Fox Television) |

Reality is underrated: Fox’s “Stars on Mars” takes off

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, July 10, 2023

I was wrong.

Five weeks ago, I wrote about the Fox space-themed “reality” TV show “Stars on Mars” and predicted that it would be awful. I based that assessment on the commercials and the advertising, and my biases against reality television, most of which is—to borrow a trope from one of the more notorious examples—garbage. I expected to hate-watch the show.

But despite the show itself leaning into the joke that the “stars” are less-than-stellar C-list celebrities, “Stars on Mars” has turned out to be better, more clever, and perhaps even more thoughtful than I expected. I won’t declare that it is great, riveting television, but it is watchable, doesn’t take itself too seriously, and doesn’t insult the viewers’ intelligence. Surprisingly, it could even teach us a thing or two about the kind of personalities needed for a successful space mission. Unsurprisingly, it is a reflection of how spaceflight, and dreams of humans on the Red Planet, are primarily entertainment, not reality.

| I won’t declare that it is great, riveting television, but it is watchable, doesn’t take itself too seriously, and doesn’t insult the viewers’ intelligence. |

My article was primarily about the long and unsuccessful history of space-themed reality shows. By my count, “Stars on Mars” is only the second space-themed reality show to reach the air (or should we say the stream?) after a string of attempts over two decades—a dozen or more proposed shows that we know about. “Stars on Mars” does not involve sending anybody to space, let alone Mars, which is probably why it succeeded in getting funded. Reality shows depend upon being cheaper than scripted television, and all the previous failed efforts proposed having an actual spaceflight (possibly only suborbital) as the prize. That would cost millions of dollars, making the show too expensive to fund (see “Red planet reality,” The Space Review, May 30, 2023.) “Stars on Mars” doesn’t have a spaceflight prize. Indeed, there is no indication of any prize at all other than being declared “the greatest star in the galaxy,” bragging rights that probably won’t get the winner a good table at a Los Angeles restaurant.

TNASA-produced art of a human mission to Mars shows terrain nearly identical to the Coober Pedy area of Australia. This location has been the site where several movies, including at least one about Mars, have been filmed. (credit: NASA) TNASA-produced art of a human mission to Mars shows terrain nearly identical to the Coober Pedy area of Australia. This location has been the site where several movies, including at least one about Mars, have been filmed. (credit: NASA) |

The Martians

The concept is simple: an initial group of 12 people is in a habitat on Mars. Things go wrong and they have to solve them as a team. Underperforming on a mission gets you sent home. The celebrities are, of course, not on Mars. They’re in the Australian outback, an area known as Coober Pedy that is bizarre and spectacular, and has been the filming site of several movies, usually those featuring either a blasted hellscape or Mars (but I repeat myself). Like a lot of Australia more than a few kilometers from the ocean, it is also rather hostile to human life, and many residents there live under ground. The show was apparently filmed relatively recently—it was supposed to last 24 days, and since it premiered in early June filming should be over by now. Filming in Australia’s winter was a necessity, because otherwise the actors would have died in their heavy simulated spacesuits, which one actor said weigh 27 kilograms.

The producers took the premise of the 2015 movie The Martian and then stretched it out into multiple episodes. Andy Weir, who wrote the book that the movie is based upon, should probably get a royalty check for this, because a number of his ideas, like a sandstorm knocking out communications and a fire destroying the food supply and requiring the astronauts to grow potatoes in human waste, are used in the show as the mission challenges that the crewmembers have to solve. Surprisingly, this premise works. None of it is very scientifically accurate—Martian sandstorms won’t knock over radio towers, and we don’t know if there’s an alien fungus on Mars that has to be burned out of caves—but neither was The Martian. Several years ago, I talked to a prominent NASA astronaut who was rather annoyed at the movie’s reputation for technical accuracy, because he thought that it was massively wrong in many ways. You have to suspend your disbelief a bit more for “Stars on Mars” than for The Martian, but not much.

There is no “I” in “team”

The show’s premise of a real space mission also extends well to the interpersonal dynamics. They are all part of a team, not individually competing against each other. The celebrities have to work together on at least one mission during each episode, and this usually involves all of the crew except for an elected base commander and a mission specialist, who both stay back in the command center to provide guidance. After returning to the habitation module, the crewmembers who did the best are declared “mission critical.” The bottom three performers are then required to plead their case as to why they should not be sent home. The missions are timed, and if the crewmembers fail to accomplish the mission before the clock runs out, then even the base commander can be sent home. Teamwork is crucial. Leadership is just as important, and culpable, as the people performing the job.

| “Stars on Mars” also looks great. The interior of the hab and the exterior terrain are filmed in vivid colors. It may not be theater-quality, but it doesn’t look cheap or silly. |

So far, the decisions to send crewmembers home have made sense. Of course, reality shows are often scripted to some extent, and they are certainly edited, so the producers were not going to show us somebody getting booted who really deserved to stay. The first person sent home didn’t work hard—or at all—on a mission. During a later episode, another slightly eccentric crewmember serving as base commander provided lots of positive encouragement during a mission but made a critical mistake by picking the wrong person to accomplish a task. The celebrity who failed the mission of retrieving water for the habitat did not get the boot—the commander who picked her did. Another celebrity was sent home because, by his own admission, he lacked focus; his mind was back on Earth, or more accurately, Los Angeles, where he had left a scandal on another reality show. Two others no longer wanted to be there: one missed his family and another found the missions too difficult. If you don’t want to participate—if you don’t want to “be on Mars”—you’re not going to do a good job.

To the show’s credit, all of the choices on who stayed and who went were consistent with what you would expect and want during a real space mission—only the most committed and hard-working people belong, and the rest are liabilities. A commander who makes choices based upon who they like rather than who is most capable is a lousy commander. A crewmember who doesn’t always do their best during an important task that the rest of them depend upon is a danger to their safety. Strength can be an asset unless the strong crewman is unmotivated. Only people who want to be there should be there. The show is logically consistent, but also consistent with the requirements of a real space mission.

“Stars on Mars” also looks great. The interior of the hab and the exterior terrain are filmed in vivid colors. It may not be theater-quality, but it doesn’t look cheap or silly. Again, The Martian clearly served as the show’s inspiration, as did other Mars-themed television series of recent years. There are indications that even some of NASA’s artwork of astronauts on Mars is based upon the Coober Pedy terrain, so it feels like Mars, because artists and movie directors have been using it as Mars for a long time now.

“Stars on Mars” started with twelve celebrities, eliminating one or more per episode. The show is filmed in the Australian outback. (credit: Fox Television) “Stars on Mars” started with twelve celebrities, eliminating one or more per episode. The show is filmed in the Australian outback. (credit: Fox Television) |

Who do you want to be stuck on Mars with?

The biggest weakness of “Stars on Mars” is the choice of celebrities. None of them are very interesting. We are lucky that nobody is overly dramatic, selfish, manipulative, or downright evil: common tropes of reality TV. But so far, none of them is the kind of person you would want to hang out with or spend time in a closed living space with—not because they are annoying, but because they are dull. At least some of that seems to be the show’s fault, because so far it has not delved into their backgrounds or who they really are beyond a very superficial level—something that is difficult to do with such a large cast.

Many of the celebrities have been in the news for some unflattering reason, and there have been slight hints that maybe there is more depth to them than the tabloid reporting has indicated. Ronda Rousey, a former wrestler, clearly likes to exercise, but appears less tough and a bit more fragile than you would expect, missing the child she left back home. Actress Ariel Winter, despite being portrayed as a bit of a dimwit in the first episode, has demonstrated that she has good observational skills and indicated that she really wanted to be there, in part to prove herself—her brief discussion of being forced into acting while very young explains why she wants to control her own narrative. Disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong so far comes across as a bit of a curmudgeonly jerk who doesn’t really like anybody, is more of a loner than a team player, but is always eager for a challenge. Are these their real personalities or selective editing? It doesn’t seem to matter all that much. William Shatner appears for about one minute per show, and none of his egotistical and self-effacing goofy charm is present either.

In a twist (you knew there would be a twist, right?) after booting five of the 12 celebrities off Mars, in episode five we are going to get four new people. Who are they? We don’t know yet. Maybe they’ll inject a bit more excitement into the show. Maybe they’re all Klingons and will try to take over the base. Unfortunately, Captain Kirk is still back on Earth, phoning it in.

Spaceflight as entertainment

Human exploration of Mars by now seems to be a consistent, if niche, part of our popular culture, a mixture of entertainment, reality, and fantasy, with very fuzzy lines between all of them. There have been television shows and many movies about explorers on Mars in the last two decades alone, and there is clearly a portion of the American public that is interested in this topic and willing to pay for and consume the entertainment.

| Much of space enthusiasm is indistinguishable from entertainment, so it’s not surprising that instead of real Mars missions, we’re going to keep getting shows that pretend that humans are on Mars. |

But Mars enthusiasm itself has been a form of entertainment for a few decades now, based upon short and selective memories (see “Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true?” The Space Review, May 1, 2017.) Many Mars enthusiasts have mostly forgotten that in the early 1990s, Bob Zubrin was going around talking about Mars Direct and saying it would be easy to put humans on Mars in a decade or so. They’ve probably forgotten that in 2014 the group Mars One was making big promises about a Mars base using the Red Dragon lander. Mars One gained a tremendous amount of news coverage—some serious, some mocking—but then it imploded a few months later, and Red Dragon never got built. And in 2016–2017, Elon Musk was predicting that a really big rocket would be putting humans on Mars by 2024, and many adulating fans took him at his word (one of them asked to go up on stage and give him a good-luck kiss). One wonders if, over half a decade later, the Mars enthusiasts are just as excited about Starship delivering cargo to low Earth orbit and maybe, someday, landing on the Moon, as opposed to settling the Red Planet. But just like the failure of doomsday to occur can often reinvigorate a doomsday cult, maybe the failure of a Mars mission to materialize can reinvigorate the belief that a Mars mission is only slightly delayed. (See “Elon Musk’s road to Mars”, The Space Review, October 3, 2016, and “Mars mission sequels”, The Space Review, October 2, 2017)

Much of space enthusiasm is indistinguishable from entertainment, so it’s not surprising that instead of real Mars missions, we’re going to keep getting shows that pretend that humans are on Mars. And it’s no surprise that the history of space-themed reality television shows essentially mirrors our own reality: take the actual spaceflight out of it and just pretend you’re in space.

With the Hollywood writers’ strike still going on and movies and TV shows being delayed, we could end up with more shows like this. That’s not what I, or really anybody, wants. But for now, “Stars on Mars” is a reasonably fun bit of summer reality sci-fi fluff.

Dwayne Day can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net .

Reality Is Underrated: Fox’s “Stars On Mars” Takes Off

The summer space-themed reality show “Stars on Mars” sends its participants on missions inspired by the 2015 movie The Martian. The show is more clever and watchable than you would expect. It airs Monday nights on Fox and streams on Hulu. (credit: Fox Television) The summer space-themed reality show “Stars on Mars” sends its participants on missions inspired by the 2015 movie The Martian. The show is more clever and watchable than you would expect. It airs Monday nights on Fox and streams on Hulu. (credit: Fox Television) |

Reality is underrated: Fox’s “Stars on Mars” takes off

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, July 10, 2023

I was wrong.

Five weeks ago, I wrote about the Fox space-themed “reality” TV show “Stars on Mars” and predicted that it would be awful. I based that assessment on the commercials and the advertising, and my biases against reality television, most of which is—to borrow a trope from one of the more notorious examples—garbage. I expected to hate-watch the show.

But despite the show itself leaning into the joke that the “stars” are less-than-stellar C-list celebrities, “Stars on Mars” has turned out to be better, more clever, and perhaps even more thoughtful than I expected. I won’t declare that it is great, riveting television, but it is watchable, doesn’t take itself too seriously, and doesn’t insult the viewers’ intelligence. Surprisingly, it could even teach us a thing or two about the kind of personalities needed for a successful space mission. Unsurprisingly, it is a reflection of how spaceflight, and dreams of humans on the Red Planet, are primarily entertainment, not reality.

| I won’t declare that it is great, riveting television, but it is watchable, doesn’t take itself too seriously, and doesn’t insult the viewers’ intelligence. |

My article was primarily about the long and unsuccessful history of space-themed reality shows. By my count, “Stars on Mars” is only the second space-themed reality show to reach the air (or should we say the stream?) after a string of attempts over two decades—a dozen or more proposed shows that we know about. “Stars on Mars” does not involve sending anybody to space, let alone Mars, which is probably why it succeeded in getting funded. Reality shows depend upon being cheaper than scripted television, and all the previous failed efforts proposed having an actual spaceflight (possibly only suborbital) as the prize. That would cost millions of dollars, making the show too expensive to fund (see “Red planet reality,” The Space Review, May 30, 2023.) “Stars on Mars” doesn’t have a spaceflight prize. Indeed, there is no indication of any prize at all other than being declared “the greatest star in the galaxy,” bragging rights that probably won’t get the winner a good table at a Los Angeles restaurant.

TNASA-produced art of a human mission to Mars shows terrain nearly identical to the Coober Pedy area of Australia. This location has been the site where several movies, including at least one about Mars, have been filmed. (credit: NASA) TNASA-produced art of a human mission to Mars shows terrain nearly identical to the Coober Pedy area of Australia. This location has been the site where several movies, including at least one about Mars, have been filmed. (credit: NASA) |

The Martians

The concept is simple: an initial group of 12 people is in a habitat on Mars. Things go wrong and they have to solve them as a team. Underperforming on a mission gets you sent home. The celebrities are, of course, not on Mars. They’re in the Australian outback, an area known as Coober Pedy that is bizarre and spectacular, and has been the filming site of several movies, usually those featuring either a blasted hellscape or Mars (but I repeat myself). Like a lot of Australia more than a few kilometers from the ocean, it is also rather hostile to human life, and many residents there live under ground. The show was apparently filmed relatively recently—it was supposed to last 24 days, and since it premiered in early June filming should be over by now. Filming in Australia’s winter was a necessity, because otherwise the actors would have died in their heavy simulated spacesuits, which one actor said weigh 27 kilograms.

The producers took the premise of the 2015 movie The Martian and then stretched it out into multiple episodes. Andy Weir, who wrote the book that the movie is based upon, should probably get a royalty check for this, because a number of his ideas, like a sandstorm knocking out communications and a fire destroying the food supply and requiring the astronauts to grow potatoes in human waste, are used in the show as the mission challenges that the crewmembers have to solve. Surprisingly, this premise works. None of it is very scientifically accurate—Martian sandstorms won’t knock over radio towers, and we don’t know if there’s an alien fungus on Mars that has to be burned out of caves—but neither was The Martian. Several years ago, I talked to a prominent NASA astronaut who was rather annoyed at the movie’s reputation for technical accuracy, because he thought that it was massively wrong in many ways. You have to suspend your disbelief a bit more for “Stars on Mars” than for The Martian, but not much.

There is no “I” in “team”

The show’s premise of a real space mission also extends well to the interpersonal dynamics. They are all part of a team, not individually competing against each other. The celebrities have to work together on at least one mission during each episode, and this usually involves all of the crew except for an elected base commander and a mission specialist, who both stay back in the command center to provide guidance. After returning to the habitation module, the crewmembers who did the best are declared “mission critical.” The bottom three performers are then required to plead their case as to why they should not be sent home. The missions are timed, and if the crewmembers fail to accomplish the mission before the clock runs out, then even the base commander can be sent home. Teamwork is crucial. Leadership is just as important, and culpable, as the people performing the job.

| “Stars on Mars” also looks great. The interior of the hab and the exterior terrain are filmed in vivid colors. It may not be theater-quality, but it doesn’t look cheap or silly. |

So far, the decisions to send crewmembers home have made sense. Of course, reality shows are often scripted to some extent, and they are certainly edited, so the producers were not going to show us somebody getting booted who really deserved to stay. The first person sent home didn’t work hard—or at all—on a mission. During a later episode, another slightly eccentric crewmember serving as base commander provided lots of positive encouragement during a mission but made a critical mistake by picking the wrong person to accomplish a task. The celebrity who failed the mission of retrieving water for the habitat did not get the boot—the commander who picked her did. Another celebrity was sent home because, by his own admission, he lacked focus; his mind was back on Earth, or more accurately, Los Angeles, where he had left a scandal on another reality show. Two others no longer wanted to be there: one missed his family and another found the missions too difficult. If you don’t want to participate—if you don’t want to “be on Mars”—you’re not going to do a good job.

To the show’s credit, all of the choices on who stayed and who went were consistent with what you would expect and want during a real space mission—only the most committed and hard-working people belong, and the rest are liabilities. A commander who makes choices based upon who they like rather than who is most capable is a lousy commander. A crewmember who doesn’t always do their best during an important task that the rest of them depend upon is a danger to their safety. Strength can be an asset unless the strong crewman is unmotivated. Only people who want to be there should be there. The show is logically consistent, but also consistent with the requirements of a real space mission.

“Stars on Mars” also looks great. The interior of the hab and the exterior terrain are filmed in vivid colors. It may not be theater-quality, but it doesn’t look cheap or silly. Again, The Martian clearly served as the show’s inspiration, as did other Mars-themed television series of recent years. There are indications that even some of NASA’s artwork of astronauts on Mars is based upon the Coober Pedy terrain, so it feels like Mars, because artists and movie directors have been using it as Mars for a long time now.

“Stars on Mars” started with twelve celebrities, eliminating one or more per episode. The show is filmed in the Australian outback. (credit: Fox Television) “Stars on Mars” started with twelve celebrities, eliminating one or more per episode. The show is filmed in the Australian outback. (credit: Fox Television) |

Who do you want to be stuck on Mars with?

The biggest weakness of “Stars on Mars” is the choice of celebrities. None of them are very interesting. We are lucky that nobody is overly dramatic, selfish, manipulative, or downright evil: common tropes of reality TV. But so far, none of them is the kind of person you would want to hang out with or spend time in a closed living space with—not because they are annoying, but because they are dull. At least some of that seems to be the show’s fault, because so far it has not delved into their backgrounds or who they really are beyond a very superficial level—something that is difficult to do with such a large cast.

Many of the celebrities have been in the news for some unflattering reason, and there have been slight hints that maybe there is more depth to them than the tabloid reporting has indicated. Ronda Rousey, a former wrestler, clearly likes to exercise, but appears less tough and a bit more fragile than you would expect, missing the child she left back home. Actress Ariel Winter, despite being portrayed as a bit of a dimwit in the first episode, has demonstrated that she has good observational skills and indicated that she really wanted to be there, in part to prove herself—her brief discussion of being forced into acting while very young explains why she wants to control her own narrative. Disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong so far comes across as a bit of a curmudgeonly jerk who doesn’t really like anybody, is more of a loner than a team player, but is always eager for a challenge. Are these their real personalities or selective editing? It doesn’t seem to matter all that much. William Shatner appears for about one minute per show, and none of his egotistical and self-effacing goofy charm is present either.

In a twist (you knew there would be a twist, right?) after booting five of the 12 celebrities off Mars, in episode five we are going to get four new people. Who are they? We don’t know yet. Maybe they’ll inject a bit more excitement into the show. Maybe they’re all Klingons and will try to take over the base. Unfortunately, Captain Kirk is still back on Earth, phoning it in.

Spaceflight as entertainment

Human exploration of Mars by now seems to be a consistent, if niche, part of our popular culture, a mixture of entertainment, reality, and fantasy, with very fuzzy lines between all of them. There have been television shows and many movies about explorers on Mars in the last two decades alone, and there is clearly a portion of the American public that is interested in this topic and willing to pay for and consume the entertainment.

| Much of space enthusiasm is indistinguishable from entertainment, so it’s not surprising that instead of real Mars missions, we’re going to keep getting shows that pretend that humans are on Mars. |

But Mars enthusiasm itself has been a form of entertainment for a few decades now, based upon short and selective memories (see “Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true?” The Space Review, May 1, 2017.) Many Mars enthusiasts have mostly forgotten that in the early 1990s, Bob Zubrin was going around talking about Mars Direct and saying it would be easy to put humans on Mars in a decade or so. They’ve probably forgotten that in 2014 the group Mars One was making big promises about a Mars base using the Red Dragon lander. Mars One gained a tremendous amount of news coverage—some serious, some mocking—but then it imploded a few months later, and Red Dragon never got built. And in 2016–2017, Elon Musk was predicting that a really big rocket would be putting humans on Mars by 2024, and many adulating fans took him at his word (one of them asked to go up on stage and give him a good-luck kiss). One wonders if, over half a decade later, the Mars enthusiasts are just as excited about Starship delivering cargo to low Earth orbit and maybe, someday, landing on the Moon, as opposed to settling the Red Planet. But just like the failure of doomsday to occur can often reinvigorate a doomsday cult, maybe the failure of a Mars mission to materialize can reinvigorate the belief that a Mars mission is only slightly delayed. (See “Elon Musk’s road to Mars”, The Space Review, October 3, 2016, and “Mars mission sequels”, The Space Review, October 2, 2017)

Much of space enthusiasm is indistinguishable from entertainment, so it’s not surprising that instead of real Mars missions, we’re going to keep getting shows that pretend that humans are on Mars. And it’s no surprise that the history of space-themed reality television shows essentially mirrors our own reality: take the actual spaceflight out of it and just pretend you’re in space.

With the Hollywood writers’ strike still going on and movies and TV shows being delayed, we could end up with more shows like this. That’s not what I, or really anybody, wants. But for now, “Stars on Mars” is a reasonably fun bit of summer reality sci-fi fluff.

Dwayne Day can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net .

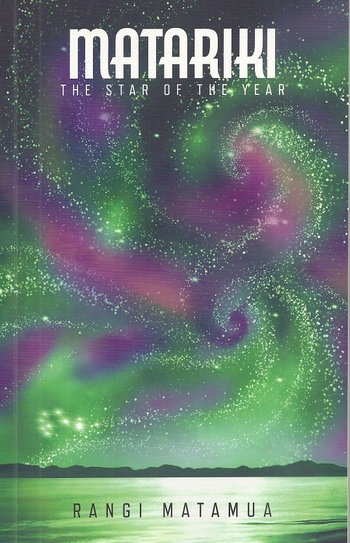

Book Review: Matariki: Star Of The Year

|

Review: Matariki: The Star of the Year

by Joseph T. Page II

Monday, July 10, 2023

Matariki: The Star of the Year

by Rangi Matamua

Huia Publishers, 2017

paperback, 128 pp., illus.

ISBN 978-1-77550-325-5

US$36.50

Since the Northern Hemisphere contains the largest portion of Earth’s human population, general astronomical texts tend to focus on the stars viewable by these peoples. One focus area that does not receive much attention outside of hard-core astronomy books are those star groupings viewable from the Southern Hemisphere, and the mythologies surrounding them. Through the voyages of Kon-Tiki and Hōkūleʻa, experiential archaeologists and cultural anthropologists have solidified the narrative about how Oceana’s sea-venturing civilizations relied upon their connection to the stars to determine positioning, navigation to their destination, and timing throughout the year. When presented to Western audiences, often these tales are viewed through (mis)translation and interpretation that dilutes the original meanings.

Inside Matariki: the Star of the Year, Dr. Ranga Matamua, a Māori professor of indigenous studies and astronomy, has created an eclectic tome on one of Oceana’s most storied astronomical phenomena. Known as the Pleiades to Western astronomers, the star cluster is also recognized as Messier object 45 (M45) or colloquially as the “Seven Sisters.” Dr. Matamua’s interest in Matariki and indigenous astronomy began during his undergraduate days, when he asked his grandfather Timi Rāwiri Mātāmua about the Māori New Year celebration around the rise of the star cluster. His grandfather produced a 400-page handwritten manuscript of astronomical observations collected by family ancestors, stretching back to the 19th Century. Toward the end of his life, Timi Rāwiri Mātāmua implored Dr. Matamua to share the astronomical knowledge, stating “Knowledge hidden, wasn’t knowledge at all.” [1]

| Matamua, a Māori professor of indigenous studies and astronomy, has created an eclectic tome on one of Oceana’s most storied astronomical phenomena. |

Within the pages of the book, Dr. Matamua weaves a tale of Matariki’s relevance from the days of Greek astronomers in the West to the varying tribes in Oceana. Introductory chapters lead readers through the eyes of the Māori people and their connection with the stars, for both travel and annual societal shifts, such as harvest and coming of winter. For mythological lore, Dr. Matamua includes a family genealogy of Matariki and her children, representing stars within the cluster. Additional tidbits of indigenous astronomy fill out the book, such as the Māori lunar calendar with identified phases, translated names of the planets, and dates of the rising and setting of Matariki until 2050 AD.

One of the most refreshing portions of the book is set near the end, presenting Māori proverbs that feature Matariki, such as:

Ko Matariki te kaitō i te hunga pakeke ki te pō

(“Matariki draws the frail into the endless night”)and

Ka rere ngā purapura a Matariki

(“The seeds of Matariki are falling”).

The former proverb details the coming of winter, where often the elderly and weak pass away, while the latter identifies when winter snowfall occurs during Matariki’s rise into the sky.

Due to its release and printing in Aotearoa New Zealand, the paperback copy has a steeper price than similarly focused astronomical mythology books in the United States. For budding cultural anthropologists interested in astronomy around the world, however, Dr. Matamua’s book will provide a refreshing view of the night sky and lore attached to the stars and is worth the purchase cost.

The article author acknowledges the Māori as the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Aotearoa New Zealand and recognizes the continuing connection to lands, waters, and communities, and pays respect to Māori culture, and to Elders past and present when reviewing this book.

References

[1] Arnold, Naomi. “The Inheritance.” New Zealand Geographic, Issue 152, Jul – Aug 2018.

Joseph T. Page II is a space historian and freelance writer located in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He is the author of Images of America: Onizuka Air Force Base (Arcadia Publishing, 2019) and Schriever Space Force Base Through Time (Fonthill Publishing, 2022). Joe can be reached at joe (at) josephtpageii.com.

An Amazing Survivor Planet

DISCOVERIES

Survivor

Scientists recently discovered a far-away planet that appears to have survived being engulfed by the rapid expansion of its dying star, Cosmos Magazine reported.

Some 520 light-years from Earth, astronomers found that the Baekdu star in the Ursa Minor constellation was burning helium rather than hydrogen.

They explained that as the star was approaching its end-of-life cycle it was expanding into a red giant that could threaten nearby planets orbiting it.

However, researchers wrote in their study that the Jupiter-like gas giant planet known as “Halla” did not get engulfed by the red giant, despite closely orbiting its host star.

“As it exhausted its core hydrogen fuel, the star would have inflated up to 1.5 times the planet’s current orbital distance – engulfing (Halla) completely in the process – before shrinking to its current size,” said co-author Daniel Huber.

Huber and his colleagues had conducted observations in 2021 and 2022, suggesting that Baekdu would at one point have been larger than Halla’s orbit. But the data confirmed the planet’s 93-day orbit has been stable for more than 10 years.

Now the question that Huber and others are asking is how did Halla survive this cataclysmic event.

Among their theories, they suggested that the Baekdu system was originally made up of two stars that “fed” off each other during the transition. This scenario prevented one of the celestial bodies “from expanding sufficiently to engulf the planet.”

Another possibility is that Halla is a new planet created when the two stars collided.

Whichever the case, it’s not certain if Earth will have the same luck when our sun becomes a red giant in five billion years.

We May Have Proof Of Extraterrestrial Life!

Regulating A Maturing Commercial Spaceflight Industry

Regulating a maturing commercial spaceflight industry

by Jeff Foust

Monday, July 3, 2023

For a change, the significance of the flight was bigger than the spectacle.

Compared to nearly two years ago, when Virgin Galactic founder Richard Branson got his long-awaited suborbital spaceflight just days before rival Jeff Bezos (see “The suborbital spaceflight race isn’t over”, The Space Review, July 11, 2021), the atmosphere at Spaceport America last week was relatively subdued. There were no huge crowds of media or invited gusts, no celebrities or musical performances. Even Branson himself appeared to be absent, at least not making any public appearances at the spaceport.

| “It was much better than expected. It was a beautiful ride,” said Villadei of his suborbital spaceflight. |

Instead, to an audience of Virgin Galactic employees, representatives of the Italian Air Force and Italy’s National Research Council, and a small number of reporters, Virgin’s SpaceShipTwo suborbital spaceplane VSS Unity took off attached to its VMS Eve mothership aircraft. The vehicles soon disappeared from view, as a stubborn cloud layer failed to burn off in the New Mexico skies. Unlike that 2021 flight, when clear skies allowed people on the ground to see Unity ascend after its release from Eve and ignition of its hybrid rocket motor, the crowd at the spaceport instead followed the flight on a larger video screen, watching the same webcast as everyone else.

Other than the clouds obscuring the view, the June 29 flight went as planned, with Unity reaching a peak altitude of 85.1 kilometers before gliding back to a runway landing at the spaceport. “It was excellent,” Mike Moses, president of spaceline missions and safety at Virgin Galactic, said in an interview after the flight. “Everything was right down the middle.”

The three Italian payload specialists on the flight (joined by two Virgin Galactic pilots and one Virgin employee in the cabin) were pleased with the flight. The three conducted 13 experiments, ranging from collecting biomedical data to combustion and fluid mechanics studies in microgravity.

“It was much better than expected. It was a beautiful ride,” said Walter Villadei, an Italian Air Force colonel who served as commander of the research activities on the flight. He notably has also trained for orbital spaceflight, serving as a backup for Axiom Space’s recent Ax-2 mission to the International Space Station. “It is a good environment and opportunity to really test all the things that astronauts are supposed to do once they get to the ISS.”

“It was an incredible experience from the takeoff to the landing,” said Pantaleone Carlucci of Italy’s National Research Council.

Despite the lack of fanfare, the “Galactic 01” flight was significant for the company, marking the start of commercial operations. (The company had generated a small amount of revenue from earlier flights, such as flying payloads for NASA’s Flight Opportunities program, but those missions were still primarily test flights.) Virgin Galactic performed this flight for the Italian Air Force under a contract signed in October 2019. The flight was, at one time, planned for early fall 2021, shortly after Branson’s flight, but the company accelerated the start of maintenance of both Unity and Eve and delayed the flight.

Now, at long last, Virgin Galactic believes it is ready to begin a regular series of commercial flights. The first flight carrying private astronauts (aka space tourists), called Galactic 02, is planned for as soon as early August, with additional flights to take place on a monthly cadence.

“We’re on that pace now where, on month-ish centers, we’ll be able to just fly again and again. We’ve got them all planned out through the rest of this year,” Moses said. “It is real to everybody now that we are doing this every month.”

That monthly pace, he said, is driven primarily by the inspections needed on the vehicle between flights. That could be shortened slightly as the company gets more experience. “While we have just this one spaceship, flying one a month is a good cadence for us.”

Mixed in with the private astronaut flights will be additional research flights like Galactic 01. Sirisha Bandla, vice president of government affairs and research operations at Virgin Galactic, said in an interview before the flight that the company is planning to conduct those research flights on a fixed schedule to help scientists plan both their payloads and their funding.

“The goal is to have it at the same time each year so that researchers can time their grants and their proposals through whatever agency funds their research and have predictable and reliable access for their science,” she said. “The number one thing that we hear [from researchers] is we want repeatable and regular access to space.”

VSS Unity is towed back to the main hangar at Spaceport America after its June 29 flight. (credit: J. Foust) VSS Unity is towed back to the main hangar at Spaceport America after its June 29 flight. (credit: J. Foust) |

Regulatory changes

As Virgin Galactic moves into a regular series of SpaceShipTwo flights, Blue Origin may be gearing up to resume flights of its New Shepard vehicle. It has been grounded since a mishap in September 2022 on a payload-only flight. The company said in March that the nozzle of the vehicle’s BE-3PM engine suffered a structural failure caused by temperatures higher than designed. That failure triggered the capsule’s abort system, which took it safely away from the propulsion module and allowed a normal parachute landing. The propulsion module crashed.

Speaking at the Investing in Space conference held by the Financial Times in London June 6, Blue Origin CEO Bob Smith said it was continuing to work with the FAA, which needed to approve the company’s investigation into the failure and plans to return to flight.

“We’re now dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s to get through that, as well as getting our system ready to go fly again,” he said. “New Shepard, from that standpoint, should be ready to go fly within the next few weeks.” The company has not provided an update on those return-to-flight plans since that conference nearly a month ago.

| “We’ve got them all planned out through the rest of this year,” Moses said. “It is real to everybody now that we are doing this every month.” |

He added that the mishap had not dampened customer interest in flying on New Shepard. “People saw a very safe system,” he said, with “a real abort scenario where the capsule came down fine and was ready to go the next day.” The company has signed up customers since that incident, but he did not disclose how many, or the backlog of customers. (Virgin Galactic has about 800 people signed up, including some who have been waiting for more than 15 years.)

Safety, while always a priority, has taken on new attention for the industry. Since the passage of the Commercial Space Launch Amendments Act of 2004, the commercial human spaceflight industry has been in a so-called “learning period” that restricts the FAA’s ability to regulate the safety of spaceflight participants on those vehicles. That period, originally scheduled to run for eight years but extended several times, allows the FAA to regulate spaceflight participant safety only in the event of an accident that kills or seriously injures people on a flight, or for incidents where there was a strong chance of injuries or fatalities.

That learning period is now scheduled to expire at the end of September, and many in industry are lobbying for another extension. “The issue of the learning period is, should the government be limited to only regulate if there is evidence requiring regulation or should they be allowed to regulate prospectively without data, without any specific reason to regulate?” said Jim Muncy of PoliSpace during a panel discussion on the topic by the Beyond Earth Institute in May.

Getting an extension through Congress in time, though, may be difficult. Both the House and Senate are working on reauthorization legislation for the overall FAA, but neither version currently includes an extension of the learning period. The House Science Committee is working on its own commercial space bill that could include an extension, but its status and prospects remain uncertain.

“We have a divided Congress, so the ability to move an extension through may be a bit challenging this year,” said Caryn Schenewerk, president of CS Consulting who previously worked on regulatory issues for Relativity Space and SpaceX, during that webinar.

| “It doesn’t mean we’re recommending a large stockpile of regulations immediately. In fact, it’s just the opposite,” said RAND’s McClintock. |

Some think the learning period—sometimes called a moratorium—should not be extended. A report issued in April by the RAND Corporation recommended that the learning period be allowed to expire this fall, but called for the gradual development of regulations by the FAA, working with industry, rather than a sudden imposition of them.

“It doesn’t mean we’re recommending a large stockpile of regulations immediately. In fact, it’s just the opposite,” said Bruce McClintock, senior policy researcher at RAND, during the Beyond Earth webinar.

FAA officials have said they do not have a set of regulations that would be ready to go on October 1 if the learning period expires. Moreover, the federal rulemaking process, with notices of proposed rulemaking and public comment periods, means it could take years for any new safety regulations to be enacted once the FAA had the authority to do so.

Walter Villadei, Angelo Landolfi, and Pantaleone Carlucci discuss their spaceflight experience during a press conference after the Galactic 01 flight. (credit: J. Foust) Walter Villadei, Angelo Landolfi, and Pantaleone Carlucci discuss their spaceflight experience during a press conference after the Galactic 01 flight. (credit: J. Foust) |

Virgin Galactic’s Moses, who also serves on the FAA’s Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee (COMSTAC), says he is encouraged by the discussions his company, along with Blue Origin and SpaceX, have had with the FAA. That’s included development of industry standards as well as planning for a new aerospace rulemaking committee at the FAA for human spaceflight occupant safety.

“The idea would be to take the data we’ve learned and use that to craft very specific, focused development areas,” he said. “We should take that in small chunks. Trying to bite off the entire regulation package at once is difficult.”

One issue, he said, is that the three companies currently flying people use very different approaches. “One set of regulations just won’t apply to all,” he said. That means crafting regulations that are more performance-based, such as requiring companies to develop restraint systems for spaceflight participants that can withstand specified loads, rather than prescribing a specific restraint system. “That’s actually a fairly easy standard to write and one to turn into a regulation as opposed to the way airline regulations are, which are highly specific to a design.”

But some in industry worry about the FAA’s ability to take on a new set of regulations as it grapples with a growing commercial space transportation industry. Schenewerk noted that companies had hoped new launch licensing regulations, formally known as Part 450, would streamline the licensing process. Instead, companies have struggled with the new rules, which have only been used for a handful of launches; most launches are under older licenses that are grandfathered in for a few more years.

“This is where experience causes some skepticism,” she said. Industry had advocated for regulatory reform for launch licensing, but the process in creating the Part 450 regulations were not as collaborative as industry liked. “I think there’s a bit of trauma around that experience that carries forward.”

RAND’s McClintock said that any development of human spaceflight safety regulations would require additional resources for the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation, or AST. One of the recommendations of the report, he said, was to “properly resource the FAA to take on this specific aspect of human commercial spaceflight regulation but also all the other aspects of oversight and support to the industry.”

Those efforts face a new complication that has to do with an incident that took place not at the edge of space but below the surface of the ocean. On June 18, a submersible named Titan, built and operated by OceanGate, descended into the Atlantic Ocean on a trip to visit the wreckage of the Titanic. An hour and 45 minutes into the trip, it lost contract with its support ship on the surface, triggering an international search-and-rescue effort. Four days later, the US Coast Guard announced it found debris from the Titan on the ocean floor. The vessel likely imploded during its descent, killing the five people on board.

| ““If you step back and look at the specifics, these are really apples-and-oranges kinds of activities,” Moses said of the comparisons of suborbital spaceflight with the Titan submersible. |

That accident has led to discussions of the parallels between spaceflight and submersibles. Both are forms of adventure tourism with similar price points—OceanGate charged $250,000 a ticket, while Virgin Galactic now charges $450,000—and prestige associated with being part of a small community of people who have either been to the bottom of the ocean or in space. Both carried significant risks, though, with questions raised about safety and oversight.

OceanGate even borrowed the language of spaceflight for its expeditions, the New York Times reported, with its customers called mission specialists; the company referred itself as “SpaceX for the ocean.” One of the people killed on the Titan last month, Hamish Harding, flew on Blue Origin’s New Shepard last year. (Stockton Rush, the CEO of OceanGate and also on board the Titan, had been interested in going to space, but said he had an “epiphany” after seeing a SpaceShipOne flight in 2004 that he wanted to be a explorer rather than a tourist.)

How this will affect commercial human spaceflight and its regulations is unclear. One industry official privately said it now seems unlikely Congress will back an extension of the learning period, concerned about the perception it is giving a risky industry a free pass from regulations.

Moses said he was not concerned that the Titan accident would affect the commercial spaceflight industry. “If you step back and look at the specifics, these are really apples-and-oranges kinds of activities,” he said. While safety of spaceflight participants is not currently regulated by the FAA, overall vehicle safety is, he noted, to protect the uninvolved public. “It certainly drives accountability. You’re not totally unsupervised.”

“Some of the things I’ve been seeing in the media make it sound like the learning period means there is no regulation. I have a multi-page license that’s been active for years and the FAA is in every single control room,” he added. “It’s a very different thing in comparison to OceanGate.”

At the Beyond Earth webinar in May, George Nield, former FAA associate administrator for commercial space transportation, tried to chart a middle ground between scenarios where there is no regulation at all and those with a large number of prescriptive regulations. The latter case, he said, might stem from a lack of trust in operators maintaining a safety culture and worries about cutting corners to save money, concerns that have been raised about OceanGate since the Titan accident.

“The question that I think we need to be focusing on is this: is it possible for us to have a commercial human spaceflight regulatory framework that takes advantage of what we’ve learned over the last 62 years of human spaceflight and encourages the continuous improvement of human spaceflight safety while still allowing advanced technologies, innovation, and new ways of doing business?” he asked. “I think the answer to that is yes.” The industry will soon find out if he’s right.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.