Lazy Cat on a mountaintop

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, April 29, 2024

In the last days of the rule of the Shah of Iran, the CIA installed a new dome atop a mountain next to a field of equipment used to gather information from inside the Soviet Union. But before the intelligence service could put it into operation in 1978, the Shah fell and the CIA hastily abandoned the site.

| Starting in the mid-1970s, the US intelligence community became more concerned about the threat of Soviet lasers to American satellites. |

The mountaintop facility was known as TACKSMAN. TACKSMAN was used by the CIA to monitor Soviet missile launches from their Baikonur missile and rocket launch facility in Kazakhstan, the same location where Sputnik and Yuri Gagarin launched into space. It was an important Cold War missile telemetry interception site. CIA officials sometimes had a knack for applying winking codenames to their projects, and this facility was a classic case, because “tacksman” is a Scottish term for somebody who paid rent to his landlord, usually a clan chief. The United States certainly paid the Shah of Iran for the use of land at his hunting palace, in return for the opportunity to hunt Soviet missiles and rockets. According to a declassified official history, TACKSMAN was primarily focused on gathering Soviet rocket signals using antennas, but it also apparently collected Soviet communications as well. But inside the dome was a telescope named Lazy Cat, also intended to look inside Soviet territory, at least when the skies were clear. Lazy Cat was designed to detect lasers directed at satellites in orbit, something that US intelligence analysts were increasingly concerned about during the 1970s.

From EGGSHELL to TACKSMAN

When it was first established in the late 1950s, the CIA’s site in Iran was code-named EGGSHELL. It was set up as a “clandestine” facility at the Shah’s hunting palace outside the city of Behshahr. It was unlike many other American signals gathering sites that were usually operated by the National Security Agency and located at American military bases on foreign soil. The first site was intended to collect communications intelligence and possibly telemetry from the Kapustin Yar missile and space launch site inside the Soviet Union. Although EGGSHELL was initially considered a “temporary” site, it soon expanded to a second location and began collecting telemetry from what the CIA referred to as the Tyuratam Missile Test Range but is today known as Baikonur. (See “Stealing secrets from the ether: missile and satellite telemetry interception during the Cold War,” The Space Review, January 17, 2022.)

Initially CIA personnel were assigned to EGGSHELL on a temporary detailee basis, but as it expanded to become a permanent site, the CIA added family accommodations and amenities. It is unclear when the name was changed from EGGSHELL to TACKSMAN, but it may have been when the second location was developed. The site, eventually referred to as TACKSMAN II and established in 1964, was much closer to the Baikonur launch complex than other US intelligence collection stations, notably a site in Turkey. Some workers stayed at the mountaintop locations overnight, whereas others commuted there daily.

Starting in the mid-1970s, the US intelligence community became more concerned about the threat of Soviet lasers to American satellites. It is unclear what initial intelligence data prompted this concern, although US intelligence agencies were aware of an active Soviet high-power laser program. According to an intelligence estimate made in early 1978, by that time the Soviet Union was believed to have a ground-based laser capability to jam sensors in geosynchronous orbit and “kill” sensors on spacecraft in low Earth orbit, up to 800 kilometers.

The Soviet Union had a large anti-ballistic missile testing facility located in Kazakhstan at Sary Shagan, on the shore of Lake Balkhash. This had been a major focus of American intelligence gathering during the 1960s. The Soviet Omega laser was installed at Sary Shagan in the 1970s but was designed for shooting down aircraft. The United States first publicly referred to Soviet laser systems at Sary Shagan during the Reagan Administration and there were rumors that in 1984 it was used to illuminate an American space shuttle. But American concern about lasers at Sary Shagan started more than a decade earlier and had prompted the development of systems to detect and measure the lasers.

| Although being sent to Florida for the summer seemed to some of the engineers to be a plum duty assignment (one even took his boat), they soon learned otherwise. |

According to the late Phil Pressel, an engineer who worked for the Perkin-Elmer Corporation, the CIA contracted the company in the mid-1970s to produce a ground-based telescope capable of detecting and analyzing lasers fired from the ground at Sary Shagan. The telescope, with a 1.2-meter (48-inch) aperture, was equipped with a sophisticated sensor that could not only detect the laser, but also determine its characteristics. It was to look for signals in the visible and infrared wavelengths: 3.7 microns, 4.3 microns, 1.06 microns, and a visible channel. Perkin-Elmer collaborated with Itek on the design and construction of the telescope, with Itek fabricating the mirror.

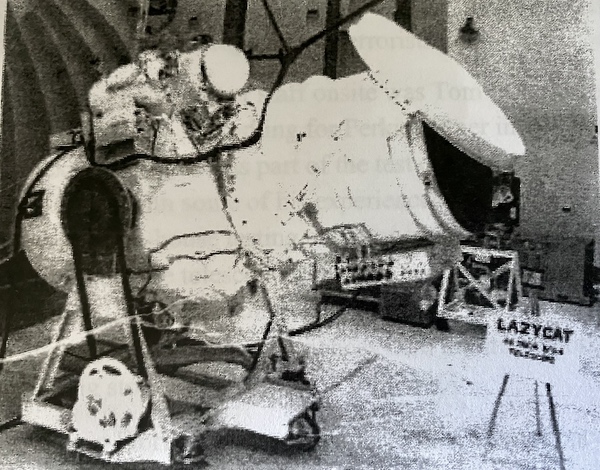

The Lazy Cat telescope was built by Perkin-Elmer and installed on a mountaintop in Iran in the fall of 1977. It was designed to detect lasers from the Sary Shagan test range when they were pointed at satellites in low Earth orbit. It did not become operational before the Iranian revolution led to the facility being abandoned by the CIA in early 1978. (credit: author) The Lazy Cat telescope was built by Perkin-Elmer and installed on a mountaintop in Iran in the fall of 1977. It was designed to detect lasers from the Sary Shagan test range when they were pointed at satellites in low Earth orbit. It did not become operational before the Iranian revolution led to the facility being abandoned by the CIA in early 1978. (credit: author) |

From Danbury to Florida

In the summer of 1977, workers at Perkin-Elmer in Danbury, Connecticut, where Lazy Cat was assembled, packed up the telescope and shipped it to Patrick Air Force Base in Florida via an Air Force C-5A Galaxy transport. Several Perkin-Elmer technicians and engineers then traveled to Florida to work on setting up and testing the telescope. Although being sent to Florida for the summer seemed to some of the engineers to be a plum duty assignment (one even took his boat), they soon learned otherwise. The company was not ready to pay them in a timely manner and left a lot of their living arrangements to the workers, forcing them to scramble when they would have preferred to simply focus on their work. They also were so busy that they didn’t have time to engage in much recreation. Lazy Cat required a lot of preparation. The goal was to test it successfully for the sponsor so that it could be shipped to Iran. Although Pressel never confirmed that the CIA was the customer, the connections were obvious because Perkin-Elmer had close ties to the agency from its work on the HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite, and because the TACKSMAN site was operated by the agency.

The telescope was set up at the Malabar Test Facility, located on Patrick and surrounded by fences and patrolled by armed guards. Lazy Cat was installed in an existing telescope dome. At one point while the telescope was being moved a small airplane flew overhead in what was supposed to be controlled airspace. The group was alarmed but could not quickly identify the plane or determine why it was overhead. They never got an answer as to whether it was an inadvertent overflight or an attempt to spot what they were doing. During setup, a thunderstorm suddenly rolled in and in the rush to secure the telescope it was dropped a small distance, damaging an electronics box. But the box was quickly fixed and the telescope was unharmed.

Setup was mostly uneventful, although the unstable local power grid proved to be a problem. During a nighttime test, the Lazy Cat telescope was pointed at an American HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite that was illuminated by a laser from the ground. Lazy Cat accurately detected the laser illumination and measured the laser’s characteristics, proving that it was ready for operation.

From Florida to Iran

Details of the telescope’s transportation from Florida to Iran in September 1977 are unknown, although it would have required a C-5 to get it there. The United States had close ties with the Shah’s government and the existing CIA facilities in the country undoubtedly had their own logistics chain.

Upon arriving in Iran, Lazy Cat was trucked to the mountaintop TACKSMAN II site. Getting it up the mountain was difficult. At one point, a crane was used to swing the trailer carrying the telescope around a sharp bend in the road. The telescope was then installed in a dome that had been built on the site next to two other domes that housed dishes probably used to track Soviet rockets and missiles. Sary Shagan was more than 1,000 kilometers to the northeast.

Several Perkin-Elmer personnel were sent to Iran to help with the installation and early operation of the telescope. They were warned by their local handlers about political instability in Iran, including a briefing about the murder of three American contractors in the country over a year earlier, and they stayed in safe houses before going to the operating location. They found the mountaintop facility to be well-equipped, with excellent food and accommodations for people working at a secret location.

| It is unknown what, if any, project may have followed Lazy Cat to try and obtain data on Soviet laser anti-satellite tests, although concern about them grew during the early 1980s. |

The Lazy Cat telescope was installed in a dome to protect it from the elements. The telescope and its systems checked out fine, working as well as they had in Florida. But there were two problems. An automated tracking system antenna dish was to provide azimuth and elevation positioning for the telescope, but it was not completed by December because of some structural issues and redesign requirements. In addition, the telescope mount also had problems moving, which burned out the controllers for the DC drive motor. Before the problems could be fixed, the key Perkin-Elmer worker sent to the site returned home, their two-month detail over. Very soon thereafter, in January 1978, the Iranian revolution took over the country. Americans at the TACKSMAN site quickly evacuated, although it is unclear if they destroyed any of the equipment that they left behind, like Lazy Cat. Phil Pressel heard a rumor that the telescope mirror was smashed with a hammer. The company’s substantial effort to build the telescope was for naught, and it never stared at the sky looking for Soviet laser beams.

In January 1978, possibly after learning about the loss of Lazy Cat, President Jimmy Carter asked for an intelligence briefing on the status of Soviet anti-satellite laser capabilities. The Secretary of Defense provided a report in February indicating that the Soviets already had a ground-based laser ASAT capability, and were developing an air- and possibly space-based laser ASAT capability. A March 1980 National Intelligence Estimate provided further estimates on Soviet laser ASAT developments. The Reagan Administration would become more alarmed about Soviet laser programs, although the end of the Cold War revealed that some Soviet laser capabilities had been exaggerated.

The closure of the TACKSMAN sites prompted a major review within the US intelligence community on how the loss of the information they gathered would affect the United States’ ability to monitor the SALT arms control treaty. U-2R and WB-57F aircraft operations were considered as an alternative means to obtain the intelligence. It is unknown what, if any, project may have followed Lazy Cat to try and obtain data on Soviet laser anti-satellite tests, although concern about them grew during the early 1980s. In 1989, a delegation of American officials visited the Terra 3 laser site at Sary Shagan—the one alleged to have illuminated the space shuttle—and found that it was a relatively low power system, nothing like the earlier intelligence reports. Ironically, the United States had a more advanced laser program.

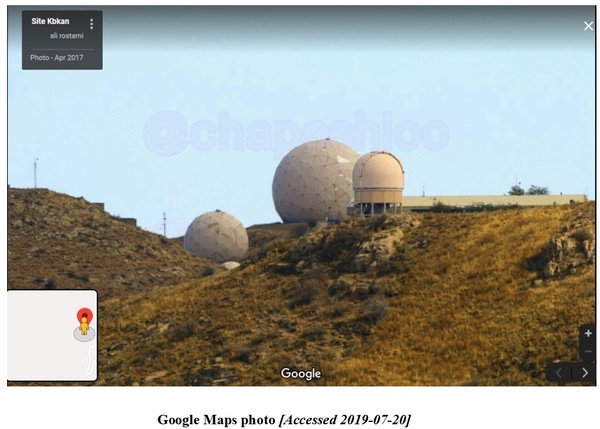

The dome on the right was built atop a mountain in Iran to house the Lazy Cat telescope. The CIA operated an array of sensors on the mountain to gather intelligence from inside the Soviet Union. (credit: Google) The dome on the right was built atop a mountain in Iran to house the Lazy Cat telescope. The CIA operated an array of sensors on the mountain to gather intelligence from inside the Soviet Union. (credit: Google) |

Today the two CIA TACKSMAN sites can be viewed with public software such as Google Earth: TACKSMAN I located at 36.6841 N, 53.5278 E, and TACKSMAN II, at 37.2963 N, 58.9131 E. Since the 1979 revolution, the Iranians have been using both locations for unknown purposes. The Iranians have never displayed the captured American facility or equipment, not even for propaganda purposes.

Author’s note: A declassified official history, The Foreign Missile and Space TELEMETRY Collection Story – The First 50 Years, written by Richard L. Bernard in 2004, included the first publicly released information on TACKSMAN. The declassified history on the National Archives website is in two parts. Part 1 covers the 1950s and 1960s, and Part 2 covers the 1970s, 1980s, and the 1990s. The TELINT history can be downloaded from the National Archives website here, here, here, here, and here.

Dwayne Day is interested in hearing from anybody with further information on Lazy Cat or TACKSMAN. He can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net.